POETRY

Stella Wong | Spooks (Dramatic Monologue as Shi Pei Pu) | Spooks (poem against the apparatus) | Spooks (disinformation tactics)

Mark Levine | Dire Offense

Gilad Jaffe | Piyyut

Lisa Low | Party Anxiety

Camille Guthrie | Victim of Love

Justin Balog | Writing Prompt

Amie Zimmerman | Entry

Maxine Scates | Animal

Steffi Drewes | from Count Like It Calms You

Ben DeHaven | RSVP

Colby Cotton | Purgatory | Purgatory | Purgatory

NONFICTION

Carol Guess and Rochelle Hurt | Night Animals

Ellis Scott | Coelacanth

Greg Wrenn | The Lantern

Amy V. Blakemore | Against Euphemism

Andrea Truppin | Leaving

FICTION

Tameka Cage Conley | from You, Your Father, a novel

James Janko| Fallujah in a Mirror

Ashley Hand | Burning Man

Suphil Lee Park | Householder

Brian Kerg | Rabbit’s Foot

Jerri Bell| He Said, She Said

Erik Cederblom| Where’s Charlie?

David Lombardi| Routes

ARTWORK

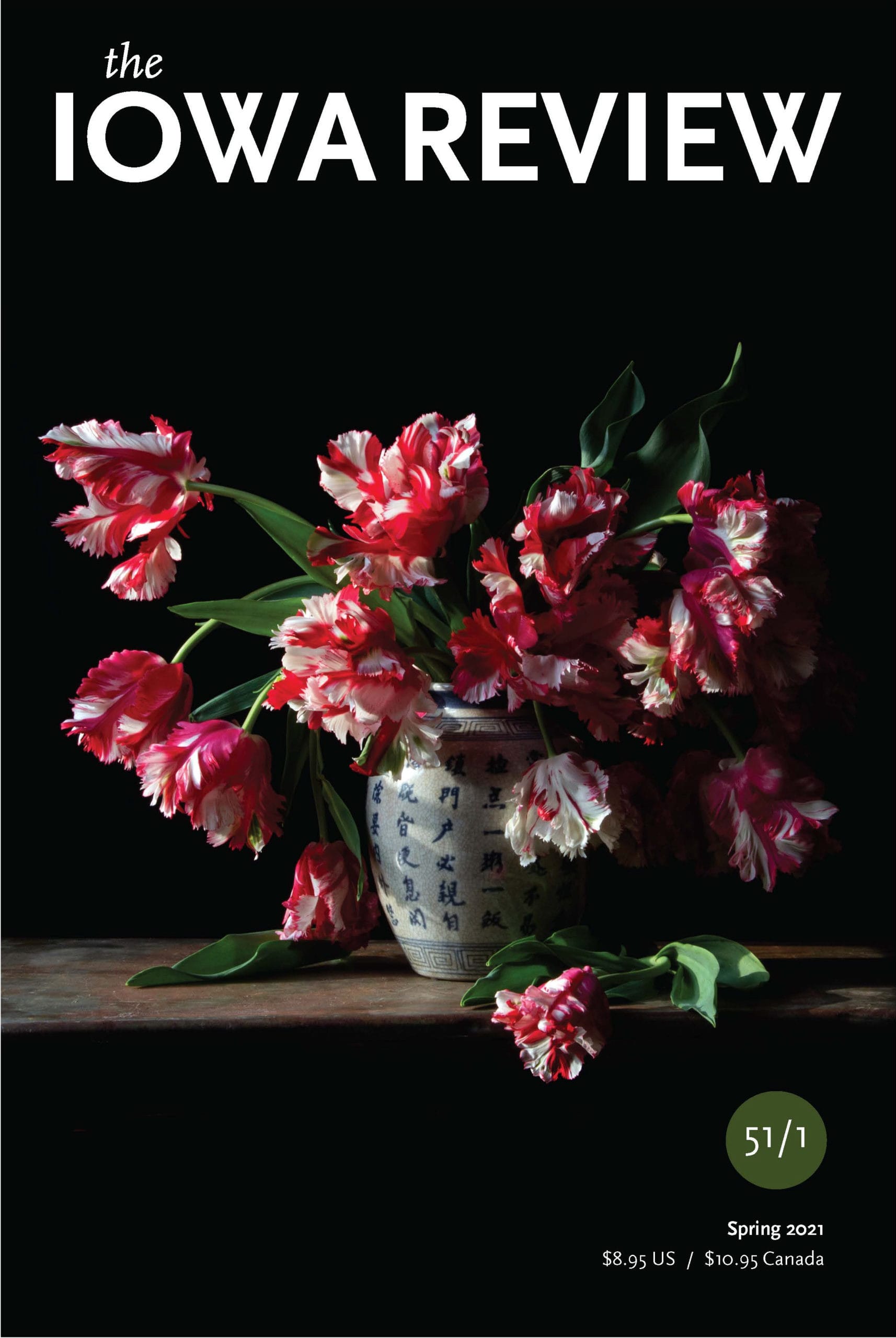

Molly Wood | Vanitas with Estella Rijnveld Tulips

Editors’ Note

Terms of Art

I love learning the exact meaning of a common word I had been using vaguely. When I temped for a marketing company in my twenties, the term “benchmark” was often thrown around at meetings. Someone finally asked, “What do you mean by that?” and someone specified: “An industry’s best practice.” At once the conversation sharpened.

When, a decade later, I volunteered at a crisis center, I learned their definition of “crisis.” The volunteer trainer described it as “a time when it is impossible to continue on the way things had been.”

People called the hotline when they were in crisis. They couldn’t afford food. Their heat was about to be cut off. They felt suicidal. They were intolerably lonely.

In their essay “Night Animals,” which begins this issue, Carol Guess and Rochelle Hurt grapple with the crisis of the early Covid pandemic. Since they wrote it, a way forward, via vaccination, seemed to emerge. But at the time of my writing (September 2021), we find ourselves in a new crisis, a variant of the first. Once again, the past no longer provides guidance, and the future is unknown.

In a series of phone calls during the height of lockdown in mid-2020, I interviewed my mother about her life story. I thought it would help her pass the time. Then I realized that what she was saying was sustaining me.

My mother was a refugee. In 1950, when she was eight years old, her family was caught in the middle of the Korean War. To flee the advancing North Korean army, her father reserved a train car in Seoul and boarded, planning to pick up his family at an outlying village, but because of the overwhelming press of refugees at the station, the train rolled through without stopping. So my mother and her young siblings and their mother, who had just given birth, walked south for weeks to stay ahead of the battlefront and to find my grandfather. Their mother carried the baby; older children carried younger children. It was January.

As I paced my floors in Iowa City, talking to her through earbuds, I felt grateful that in the current crisis, I still had my home; my family was together; we were warm; we had food.

I also talked to my uncle. The oldest son, he was expected to step into the role of man of the house despite being only fourteen. On the most miserable day, as they trudged along an icy river, he considered whether it would be better if they all threw themselves in. The next day they came upon a house. They knocked, and a woman answered. She saw them in their weather-beaten clothes, looking like beggars, and almost shut the door. Then she saw the newborn.

The woman let them stay in a room of her house and gave them food. From there they made it to a town where they were able to get word to my grandfather. Having assumed his family was dead, he had just shaved his head in preparation to join the army, figuring he had nothing left to live for. They reunited and started a new life in Pusan until the armistice.

I asked what lesson my uncle took from the war. “Don’t give up,” he said. “One foot in front of the other until you can go no more.”

This issue also contains fiction by the five winners of our veterans’ writing contest. Like my mother’s family, characters in these stories seek a way through the crisis of war, but war itself is not the only crisis in this group of winning works. There is the crisis that follows war—in a marriage struggling after a veteran’s return, for instance—or the ongoing crisis of sexual assault not brought to justice in the military.

As those works and so many of the other stories, essays, and poems in this issue show, daily life contains its crises as well; they are not always national or worldwide events (or even if they are sparked by such events, the authors chronicle repercussions at the individual level). A woman loses her father in a plane crash; a boy steps forward to kiss another boy; a traveler falls in love in the time of AIDS.

Why read a literary magazine in a time of crisis? I can only answer for myself. Experiences shared, via words used intentionally, artfully, and with precision, are what will get me through this crisis, and the next.

Lynne Nugent