In anticipation of an upcoming visit to Iowa City and public lecture by acclaimed music writer Greil Marcus, TIR asked Kembrew McLeod to pose a few key questions to him. Topics ranged from canonization to adaptation to populism, from Donald Trump to Bob Dylan to Lady Gaga.

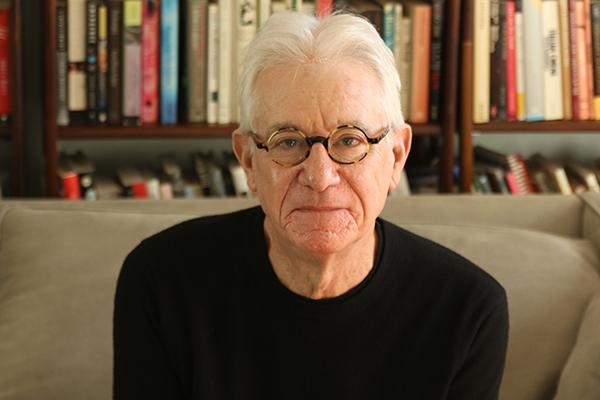

Greil Marcus served as Rolling Stone’s original reviews editor and has since written and edited more than fifteen books on music and American culture. He is the author of the seminal work Mystery Train: Images of America in Rock ’n’ Roll Music, called “the book that launched a thousand rock critics” by the New Yorker, and “perhaps the finest book ever written about pop music” by the New York Times Book Review. Marcus has been a contributor to the New York Times, Esquire, Creem, Village Voice, Artforum, Salon, the Believer, Pitchfork, and others.

His public lecture is being sponsored by The Englert Theatre, Prairie Lights Bookstore, The Iowa Review, and the Tuesday Agency, as well as the University of Iowa’s Nonfiction Writing Program, Department of English, College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, and Provost’s Office.

Kembrew McLeod is a professor of communication studies at the University of Iowa. He has published and produced several books and documentaries about music and popular culture, and his writing has appeared in the New York Times, Slate, and Rolling Stone; McLeod’s most recent book, on Blondie’s Parallel Lines, was published by Bloomsbury in its 33 1/3 series.

This interview took place via e-mail on October 17, 2016.

Kembrew McLeod: You have written entire books on the works of a single artist (Van Morrison and The Doors), and even a single song (Bob Dylan’s “Like a Rolling Stone”). When you are considering an artist or cultural text for an in-depth analysis, what qualities do you look for?

Greil Marcus: I don’t approach it that way. I’m not making a judgment about who or what is worthy of that kind of sustained attention. The “Like a Rolling Stone” book was a publisher’s idea. I rejected it because I didn’t think a whole book on one song was a good idea (before or since there have been quite a few) and because I was in the middle of writing another book. My wife countered that the publisher didn’t know “Like a Rolling Stone” had been my favorite song since it appeared in 1965 and as the publisher was looking for a book, not necessarily me (the occasion—this was 2004—was the looming fortieth anniversary of the release of the song, which didn’t seem that big a deal to me—who cares about fortieth anniversaries?), if I didn’t do the book someone else would, and how would I, so speak, feel about that? So I said yes. With the Van Morrison book it was a hunch that there was a book, just merely a set of pieces, in looking at his work in pieces. That book was fun to write, and then when I found the radio was all over The Doors in 2009, so long after they’d disappeared, I wanted to understand that story. So there was no attempt to add to or construct a canon. It was a matter of wanting to write and being lucky enough to find subjects.

KM: Speaking of Bob Dylan, what are your thoughts on him recently winning the Nobel Prize for literature, and were you surprised that some were critical of that decision?

GM: Dylan winning the Nobel Prize for Literature is a cause that many have pursued for at least twenty years. He is nominated every year—whatever that means; I always thought the Swedish Academy selected their own contenders—I assume by some very distinguished, academically legitimate people. The idea always struck me as silly. It wasn’t necessary for him and, as with so many recent prizewinners, the world didn’t need to be alerted to the interesting work of this obscure artist. But when I heard about it I was surprised at how happy it made me. I was happy for Bob Dylan. Given his extraordinary MusiCares speech—forty-five minutes of irresistibly charismatic score-settling and artistic self-analysis—I’m looking forward to hearing what he has to say when he accepts it. I wasn’t surprised at people who rejected it, but I’ve yet to read a critical piece that hasn’t seemed small-minded and self-erasing. Jodi Picoult tried to make Dylan as Nobelist seem absurd when she asked if this meant she could now win a Grammy—sure, Jodi, write some liner notes, no one will stand in your way.

KM: If lyrics can be literature, do you think cultural criticism can also be literary?

GM: How can cultural criticism NOT be literary?

KM: You have a deep interest in history and culture—and in “old, weird America,” as you have put it. Are there any moments in time we can look to for wisdom about the new populism and the rise of Donald Trump?

GM: If by moments in time you mean the past, as in looking for precursors, sure, there are countless thousands: race riots, populist rages, demagogues, lynchings, assassinations. And yet if you look beyond such sadists as Father Coughlin and Gerald L. K. Smith—both of whom were fundamentally classic anti-Semites more than anything else—to figures to whom Trump has been compared, such as Tom Watson or Huey Long, you’ll find that they began as reformers, truly were outraged on behalf of the voiceless and powerless, and only later—not that it necessarily took that long—fell victim to their own egomania. There’s no such empathy in Trump. I’m a great believer in the notion that there are always new things under the sun, and I think Trump as a face of the nation or a political leader is something new. That he has brought into the light, without any glossing, the size and commitment of the America that, from my point of view, hates America, is unparalleled.

KM: With that in mind, is there a song you can think of that provides an appropriate soundtrack for our newer, weirder America?

GM: Lady Gaga, “Bad Romance.”

KM: Your book Lipstick Traces has been turned into a play, which I saw in 2001. In an ideal world, with no budgetary or logistical constraints, which one of your other books would you like to see adapted, and for what medium? The sky is the limit—be bold!

GM: I don’t have to be. In 2014 the Comédie Française staged their “Comme une pierre qui . . .”, an adaptation of my “Like a Rolling Stone” book in Paris, and it was thrilling, upsetting, dark, explosive—you could barely keep up with it. They will be restaging it across France and in Paris next year. I can’t imagine an adaptation anywhere near so gratifying. People have approached me about a Lipstick Traces film over the years, and I’ve told them what I told the Rude Mechs in Austin when they raised the idea of a theatrical version: “Go ahead, see what you come up with.” But nothing has come of that. I have done theatrical readings of a play I wrote, putting all of the characters, settings, and themes of the book [Lipstick Traces] on the stage of a single nightclub—something I wrote before starting to write the book, to round up the characters and introduce them to each other, sort of—but the best adaptation of the book I know is that of a woman who was so struck by the death’s-head variations in a collage by George Grosz that is included in the book that she had them tattooed all over her body. And they were beautiful: