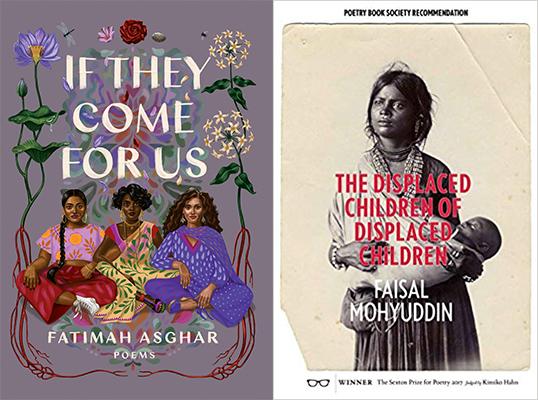

Partition. Migration. Trump’s America. These are among the themes of Faisal Mohyuddin’s and Fatimah Asghar’s respective debut full-length collections: The Displaced Children of Displaced Children and If They Come For Us. Mohyuddin is a teacher and writer based in Chicago, and Asghar is a performer known for writing the Emmy-nominated web series Brown Girls. Having descended from Pakistani immigrants to America, both poets—in lyrics at times melancholic and wistful, at others fiery and irreverent—reckon with violent, map-changing histories. The subcontinent’s 1947 Partition into independent Pakistan and India figures prominently, but so do questions about what it means to be Pakistani American, especially after 9/11 and the 2016 presidential election. These collections, with their deftly rendered cogitations on exile, displacement, and longing—particularly through the ghazal, a form originating in Arabic, Persian, and Urdu verse—recall Kashmiri-American poet Agha Shahid Ali, who first popularized the ghazal in English. Mohyuddin and Asghar, with these promising debuts, have already established themselves as Shahid Ali’s heirs.

What strikes the reader first in Mohyuddin’s The Displaced Children of Displaced Children, which received the 2017 Sexton Prize for Poetry, is the case it makes for the inextricability of South Asian culture from the American context. The following verses from a ghazal by Allama Muhammad Iqbal (1877–1938), a poet-philosopher who influenced the Pakistan Movement, first greet the reader in an epigraph:

We have come to know our existence can never be erased

Even though, for centuries, history has been our enemy.

Iqbal, we have no confidante in this troubled world—

So what can anyone know of our hidden anguish?

The epigraph not only testifies to the attempted erasure of British India’s Muslims, who then rallied for a state of their own—Pakistan—but also to the presence of South Asians in the U.S., anticipating the book’s larger premise that South Asian Americans were part of this country’s social fabric even before independence and Partition. Mohyuddin intersperses poems about his own parents’ lives before and after Partition, as well as their stories of migration to America, with poems about historical South Asian and South Asian American figures.

In “Bhagat Singh,” Mohyuddin pays homage to the important Indian revolutionary (1907–1931) who was executed by the British for attempting to assassinate a police superintendent. He writes: “Bhagat heard / the voices of Douglass and Du Bois, / and he wept at the sheer nobility of the oppressed, / be they Indian or American, and thereafter / he resolved to die a free man.” Thus American and Indian revolutionaries unite against European imperialism, connecting transoceanic movements for self-determination. This is perhaps demonstrated most heartrendingly in “Denaturalization: An Elegy for Mr. Vaishno Das Bagai, an American,” a piece eerily timely given recent attempts by the Trump administration to strip citizenship from even immigrants living here legally. Mohyuddin relates the story of Mr. Das Bagai whose citizenship was withdrawn following United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind, a 1923 Supreme Court decision which denied citizenship to Indian Americans born abroad because they were not considered white. Das Bagai committed suicide in 1928 in San Jose. “His was a different / displacement,” Mohyuddin writes, “hovering along the blade-edge of grief, / banished on account of his unchangeable blood.”

These images of blood and belonging are repeated in the closing poem to signal that survival is possible. “Song of Myself as a Tomorrow,” with its observations on erasure and displacement, brings us back to Iqbal’s epigraph but also to Whitman, a figure to whom Mohyuddin pays strategic homage to in order to reassert his own Americanness. The speaker is hopeful: “But erasure— / what can it do when the blood’s trajectory / has forever been about becoming another river, about winding its way / along some other pathway toward survival?” The collection ends, triumphant: “Yes / to exile / Yes / to America.”

This allusion to Whitman also rears its head in Fatima Asghar’s debut, If They Come for Us, a much more gendered rumination on the conditions of being South Asian and Muslim in America. Consider the title poem at the end of the collection in which Asghar channels Whitman’s line “I contain multitudes”:

a dance of strangers in my blood

the old woman’s sari dissolving to wind

bindi a new moon on her forehead

I claim her my kin

In addition to claiming the Hindu woman as her kin, she also embraces “the Sikh uncle at the airport” and “the Muslim man who sips / good whiskey at the start of maghrib.” The speaker proclaims: “mashallah I claim them all / my country is made / in my people’s image / if they come for you they / come for me too,” thereby laying down a manifesto for solidarity among marginalized identities. Her unapologetic use of “mashallah” is just one example of how Asghar weaves Urdu, Arabic, and English lexicons into her work to create a distinct Pakistani-American poetic sensibility. Such formal strategies, in addition to proficiency with the ghazal form and musings on Partition and migration, bear much in common with Mohyuddin’s poetic ethos. However, Asghar’s work is unique because it brings questions of gender and sexuality into the mix.

As Asghar’s introductory note about Partition reminds us, it is the violence toward women during this catastrophe that she considers especially traumatic: “An estimated 1 to 2 million people died during the months encompassing Partition. An estimated 75,000 to 100,000 women were abducted and raped.” Thus, poems like “Shadi” (Urdu for wedding), pray “may our names / come before / our sex,” and “one day may / the men in our beds / not be strange.” But there are other poems like “Boy” and “Other Body” that bring the trope of dislocation to bear on gender itself as the speaker engages with her queerness: “I have a boy inside me & I don’t know / how to tell people.” Asghar, an orphan, asks: “Mother, where are you? How would / you have taught me to be a woman?”

Asghar wrestles with the death of both her parents in her other poems as well, a reality that brings a personal dimension to her political poems, and the events of the political sphere find parallel expression in the domestic. In one of her many poems titled “Partition,” she recalls how “Ullu,” presumably an uncle, “partitions the apartment in two” and thus separates the speaker and her sisters from her aunt. She writes: “Allah made a barrier between me & my mom. / Ullu makes a barrier between me & my aunt.” In “The White House,” she recounts how she and her sisters hid in an off-white toilet “when Ullu was in a bad way.” In such poems, the political violence of partition and that of the current administration find microcosmic expression in the home, and Asghar reasserts the importance of gender in historical and current politics.

Together, these poems constitute a long-awaited collection that bears witness not only to the Muslim- or Pakistani-American experience, but one viewed through the lenses of gender and sex. Like Mohyuddin’s collection, it attests to the centrality and relevance of Pakistani voices in contemporary American literature.

by Fatimah Asghar

One World, 2018

$16; ISBN: 9780525509783

128 pages

The Displaced Children of Displaced Children

by Faisal Mohyuddin

Eyewear Publishing, 2018

$14.44; ISBN: 1912477068

88 pages