Toward the end of Erik Martiny's The Pleasures of Queuing its narrator writes, “There should really be a literary prize for the best novel ever written by a writer afflicted with ADD who has radios broadcasting from every room in the house, every area of the brain, an exponential, incremental number of siblings, a hawk-watchful mother, and an increasingly eccentric and money-stinting father.” This sentence describes some of the most appealing qualities of the novel. It can hardly be said to have a sequential plot; nor can it, despite one chapter being devoted to each of its narrator’s first twenty-four years, exactly be described as a Bildungsroman. Each chapter plunges into a different topic—infestation by fleas, dismantling and rebuilding a 2CV in the house, a kleptomaniac girlfriend who urinates in every receptacle in the house, infantile incest. It coheres mainly by virtue of its exaggerated, Rabelaisian portrayal of family life: this is the novel’s warm, pulsing heart. The sentence also tells us that this is a highly self-conscious, self-referential, literary novel. It opens with an account of the narrator’s conception, and the allusion of Tristram Shandy is characteristic. Each chapter opens and closes with a list of world events in the year in question; the narrator correctly guesses that the reader will interpret this as “a postmodernist whim,” which he half concedes but claims it also represents the French radio news bulletins that pervaded the family home.

French because the father is “a Frenchman of archetypal proportions,” a hypersexual but uxorious soixant-huitard whose marriage to a devout but equally sexually enthusiastic Irishwoman produces approximately twenty-four children. The evocation of the increasingly thronging household, with its consequent forced intimacy and plethora of bodily fluids, is what gives the novel life. It is grotesque in the Bakhtinian sense, its most memorable episode being the father’s way of coping with his wife’s breast-milk, too abundant even for her many offspring. Being a hoarder, an environmentalist, and obsessively hostile to waste, he manufactures yogurt and cheese out of the excess—not to mention feeding his children placenta burgers. At its best, the novel’s language, inventive and exuberant, echoes this abundance. The title refers ironically to the necessity of waiting one’s turn for everything in such a household, especially the toilet. The emphasis is on the inconveniences, discomforts, and squabbles inevitably generated in a large family, and grotesquely magnified in this one, but the dominant feeling is nevertheless one of love and vitality: “the happiest and most fully functional dysfunctional family I know.”

It may be that the book’s soft center, its overflow of fertility, milk, semen, urine, and every imaginable fluid, and the emotional equivalent, made it need a carapace of postmodern smartness. By the same token, halfway through it I was inwardly congratulating the author on not writing a Bildungsroman but allowing his narrator to take second place to the family which is normally left behind in such narratives. Later chapters do take more conventional form, with episodes devoted to the hero’s education, foreign travel, and, of course, experiences with women. The dominant mode of these however is still Rabelaisian—the performance-artist girlfriend who manipulates eggs and vegetables in her vagina, the one who urinates in his mother’s handbag, or, most memorably, his capture by a group of German skinheads who get him drunk and persuade him to join in a protest against the half-demolished Berlin Wall that I will leave the reader to discover.

The tendency of the novel to drift into a kind of Bildungsroman, and its postmodern literariness, come together in the disappointing last chapter where, on a ferry to France with intention of writing a novel while living on the roof of a building or under a bridge, he encounters his literary heroes and heroines enjoying a kind of Olympian afterlife in the form of a sauna. This is so knowing that it almost turns itself inside out, and this reader is left returning to what the hero is leaving behind, and to the insistence that “love is a greasy, blissfully smelly thing . . . Don’t forget that, poor brain-washed reader, you know it in your heart.”

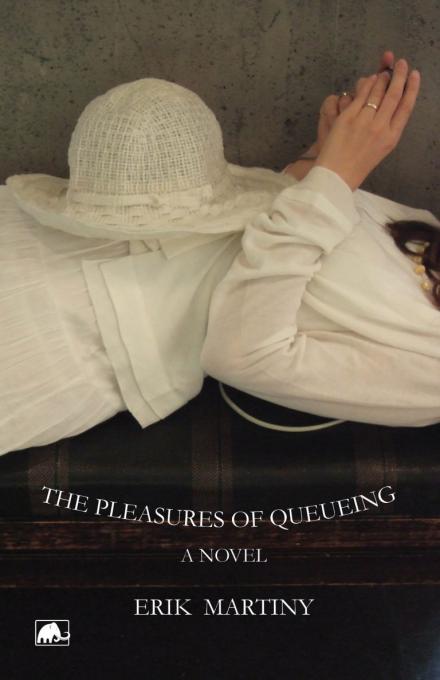

by Erik Martiny

Mastodon Publishing 2018

$18; ISBN: 978-1-7320091-1-0

206 pages