In March 2011, an earthquake and tsunami in Japan created the worst nuclear disaster since Chernobyl. A series of meltdowns at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant in Okuma forced nearly 150,000 people to evacuate a “no-go zone” of some 600-square kilometers. The intensive cleanup effort is expected to take upwards of thirty years and around 45,000 people remain displaced.

However, the disaster could have been much worse. As the plant was being evacuated, a group of workers stayed behind to stabilize the reactors as best they could, risking injury, exposure, and death. Dubbed the “Fukushima 50” by the media, though more than fifty were eventually involved in the efforts, these workers prevented a nationwide catastrophe.

Titled to evoke classic Godzilla movies, Lee Ann Roripaugh’s collection tsunami vs. the fukushima 50 honors these workers and other survivors of the disaster as sci-fi mutant heroes, likening them to the Hulk, Radioactive Man, and Mothra. She prefaces her collection with a quote from the 1985 sci-fi classic The Return of Godzilla: “When man falls into conflict with nature, monsters are born.” These monsters include boars with “cesium 137 / disco-glittering their veins” and “the dog that doesn’t know it’s dead.”

Roripaugh introduces readers to her tsunami, an avenging “annihilatrix,” in a series of poems woven throughout that explore its many facets. A “cobra come uncharmed,” the tsunami smashes through the “barbed wire that interns her,” a reference to the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II. Full of rage and desire, it is a decidedly female force “cross-dressed in high femme,” whose “terrible radiance” emanates from a deeply wounded self. Roripaugh writes, “Her superpower a wound . . . the language of wounds to wounds.”

By returning again and again to the figure of the tsunami as a “misguided kwannon,” a “shapeshifter,” a “French poststructuralist,” and an emo kid, Roripaugh is staging repeated attempts to find language for wounds and woundedness. The need to keep trying out new guises for the tsunami’s destructive powers simultaneously points to language’s creativity and insufficiency in the face of disaster.

The tsunami “remains unnamed / call her the meme / infecting your screen.” The effort at naming is revealed in the thickness of Roripaugh’s language. When the tsunami sleeps, she dreams of “fishes helixed / in spiraling schools / anemone’s veronicas / ouroboros of sea snakes,” and when awake she unleashes “a plump of cummerbunds / a wedge of polystyrene / an ostentation of aerosols.”

And yet, when Roripaugh narrates the experiences of survivors, her language is more pared down. Readers feel the weight of loss in the simplicity of a father’s words wishing he had the strength to cling, to have been “strong enough / to hold on to what matters.”

In comic books, superheroes are awakened by trauma and loss. Peter Parker fails to save his uncle from a car-jacking, Batman witnesses his parents gunned down in an alley, and Superman’s home planet is destroyed. Comic books alchemize trauma into power. Similarly, in tsunami vs. the fukushima 50, characters dream of superhuman strength, the ability to fly, or magical armor in the catastrophe’s wake. A displaced girl, one of the “nuclear diaspora,” wanders the streets thinking of the X-Men character Armor: “If she feels fragile or upset, / her armor can expand to the size / of a giant space alien lizard.” A man searches for his lost daughters in contaminated wreckage with such persistence he earns the nickname “The Hulk.” Upon seeing a sign that reads “Nuclear Power: Bright Future / of Energy,” he remarks, “I feel such a huge / surge of adrenaline and rage, / that I have to tear it down.” A man made radioactive because, with no one willing to take him in, he stays in the no-go zone and cares for abandoned animals, imagines becoming a “superhero through / a radioactive ostrich bite.” However, this Hulk never finds his daughters, the refugee can’t protect herself from violence, and the Radioactive man remarks, “I remember I can see my future / in the sick animals I care for.”

The Hulk’s rage is fueled by the fact that this disaster was “as it turns out, preventable.” (An investigation revealed that the plant operator didn’t meet basic safety requirements or perform a thorough risk assessment.) Roripaugh drops hints of this failure and failures in the response with details like people cleaning up containments with paper towels. The refugee girl remarks about her camp, “They call it temporary / but it’s been two years.” There are also subtle moments of irony, like the girl buying her grandmother oranges imported from Hiroshima because they are safe to eat.

One of the most remarkable characters in the book is a seventy-eight-year-old pearl diver, a woman who has spent her life diving for oysters without the aid of equipment: “I made a final image / of my life to tie myself to / like a wooden buoy, took / one long deep breath, and dove / back into the sea again.” Here Roripaugh offers of a powerful image of a woman refusing the conflict with nature and surviving by diving in.

“Safe is just another empty signifier,” Roripaugh writes. She ends the collection with a list of disaster-related words that she redefines, turning “arrival time” into “when she rolls up to your door with seaweed salad and fresh tofu in a bucket / a pulsing bouquet of jellyfish” and “s-wave” into “tsunami’s gangsta name.” In doing so, she engages in language’s power to transform and resignify, a gesture of hope that the word “safe” could be filled again with meaning. Though her last three entries read “(empty),” marking the limit point at which language fails.

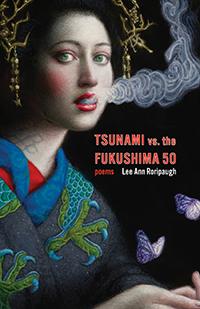

tsunami vs. the fukushima 50

by Lee Ann Roripaugh

Milkweed Editions, 2019

$16 paperback; ISBN: 978-1-57131-485-7

120 pages