My mother divorced when I was six months old and remarried when I was twenty-eight. Even with a handful of kids, my salsa-dancing, surfer-girl mother was a catch. And so a parade of men took my mom out on dates, attended our birthday and Christmas parties, and sat through our recitals and school plays. My siblings and I were generally welcoming of our mother’s current beau—until the breakup. Then the man was simply written off and forgotten. I remember no sadness around these events.

Though I fancy myself a fairly empathetic person, the first time I considered my mother’s boyfriends’ points of view occurred only after reading Paula Carter’s No Relation. What was it like to enter into our family unit? What was it like to leave? Did any of her boyfriends think of us after, wondering who we grew up to be?

A memoir told through flash nonfiction, Carter’s debut book deftly relates her story of dating and falling in love with a single dad and his two boys. Sometimes a girlfriend and lover, sometimes a Red Cross–certified babysitter, and sometimes just “poopy Paula,” Carter tenderly leads her readers through her dynamic relationship and eventual break up with this family. Through these petite and well-crafted essays, she reflects profoundly on the larger themes that loom over the romantic relationship, such as the nature of memory, her own identity as an “almost mother,” and the constellation of unnamed and uncategorized relations that she builds while dating a single parent.

The unique form of this memoir serves the narrative well as it mirrors the disjunctive experience of playing so many roles for so many people tangential to her boyfriend, as well as the other side relationships that develop—like when the boys start to call her own parents grandma and grandpa without any prompting by an adult. In one particularly moving sequence, Carter writes about her alliance with the boys’ mother. In a moment of need, their mother turns to Carter and asks for help. To convey the emotion of this event, the author describes the anatomy of animal hearts: the hummingbird heart fluttering rapidly versus the spacious, attic-sized heart of a whale. Then she writes: “My tiny bird heart had been clipping along, and then I was standing in it.”

Many readers do not expect memoirs to maintain such a high level of poetic prose throughout, but in each of these short essays, the language is precise, chiseled, and crafted to sing. As a reader, I felt I was in capable hands, and so I willingly followed the author into the more experimental essays—such as the essay that uses footnotes to carry the narrative forward, or the one that directly addresses Octavia, the abandoned wife of Mark Antony, who raised her own children alongside the children from his affair with Cleopatra (“Octavia, Octavia. What kind of woman you must have been”), or the essays that reimagine the witchy stepmother of fairy tales, or the snarky rewrites of self-help books aimed at assisting women that love a man who will always be most loyal to his children.

Carter’s skillful language work carries through to the essays that hardly appear like prose on the page, borrowing instead the form of augmented entries of the Oxford English Dictionary. A slant attempt to understand her own role as stepmother, in the essay “Steop,” Carter meditates on the etymology of the prefix “step” and its cousins:

Astíeped: bereaved in Old English

becomes

Steopan: to bereave

becomes

Steop bearn: an orphan child, bereft of one or both parents

. . .

Bereave: to deprive, rob, strip, dispossess, mostly of immaterial possessions like life and hope.

Steopfaeder: hopeless father

. . .

Foster—festermoder: a woman who cares for a child not her own.

Fester. Fester.

Fester: Of a wound or sore; to become a fester, to gather or generate pus or matter, to ulcerate.

Festermoder: A woman gathering pus.

As seen in the above excerpts, the experimental form allows the author the space and distance to view the historied role of an “almost mother” and, further, uses the research to convey the little-discussed undertones of stepmotherhood she experiences presently.

While flash nonfiction is not a new genre, it is becoming increasingly popular, with the development of many new literary journals completely dedicated to the form or featuring it in special issues. Book-length collections that build on the flash essay, however, are rarer, with only few titles besides No Relation published in the last twenty years, including Abigail Thomas’s Safekeeping (2001) and Beth Ann Fennelly’s Heating and Cooling: 52 Micro-Memoirs (2017). It is interesting to note, that like Carter’s memoir, both Thomas and Fennelly’s books relate stories of family life and the raising of children. Perhaps there is something inherently motherly about the form, or perhaps the multifaceted demands of motherhood find home in focused, short bursts of creative work. Whatever the reason, I am excited to see how it develops in the coming years, as I believe it will continue to grow in popularity and to follow the work the emergent writer Paula Carter.

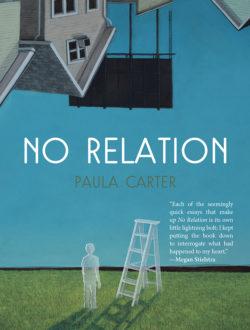

No Relation

by Paula Carter

Black Lawrence Press, November 2017

$15.95 softcover; ISBN: 978-1-62557-981-2

115 pages