Years ago, when I read William Carlos Williams’s collection of poems Spring and All (1923), it was the first time I experienced a poet who tried to teach people how to read his poetry in his poetry. “So much depends” is the center argument of his book-length tutorial:

so much depends

upon

a red wheel

barrow

glazed with rain

water

beside the white

chickens

Pretty much, if any one of these objects in his poem were placed in a different scenario, our picture would change. That is why “so much depends.” With Williams, as with many Modernist writers who desperately wanted to be more direct, the objects inhabit a relativity. But being direct isn’t necessarily easy.

TS Eliot played around with Freud in his personas, like Prufrock measuring his life in coffee spoons.

Ezra Pound took the layers of nineteenth-century symbolism and stripped his poetry to acetic precision (and he was a ruthless critic of Walt Whitman).

Gertrude Stein made inanimate objects kinetic (no lazy nouns, please) and extremely personal to the point that we become voyeurs in a place not meant for us, like Mr. Furley hearing Jack, Chrissy, and Janet install a shower curtain behind a closed bathroom door. “You need to bend over further, it won’t fit at this angle.” Stein’s poems are an inside joke, and we are still trying to decipher the punchline.

Faulkner created surface chaos with larger, underlying meaning: a Picasso painting in letters. Stitch the random pieces together, and there is a linear narrative. You just have to work for it (no lazy readers, please).

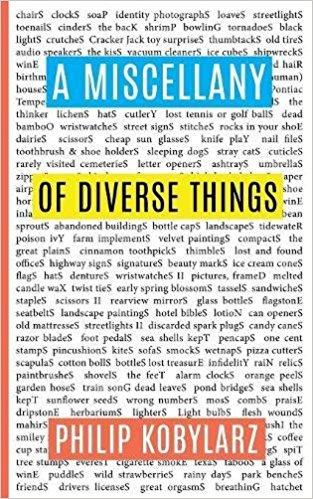

Philip Kobylarz’s 2017 collection, A Miscellany of Diverse Things, is a puzzle to be solved—not on the page, but within ourselves. The collection of vignettes wander somewhere in between haiku and a series of dictionary entries.

What we discover is that these objects are in no way miscellaneous. Kobylarz implies that these objects are part of our lives, and they are triggers for our own internal poetry. We are not the masters of these objects; rather, they are the muses of our lives. What makes these objects “original” is that they are only truly seen for just a moment in time. Each vignette is like finding the rainbow in sprinkler mist—it only reveals itself in light at certain angles. Kobylarz attempts to capture the prism of objects and what they really mean to us.

Unlike Ambrose Bierce’s Devil’s Dictionary (1906), Miscellany removes the vitriol and judgment. Each “thing” in Miscellany holds a certain objectivity, but also a humor without cynicism. Each object never strays from its intended purpose—chairs act like chairs. Maps act like maps. It is our experiences with these objects that creates meaning and importance. The personifications of each object is the spirit of Man, in all of its glory and embarrassment.

Kobylarz plays omniscient while offering us a canvas of words where we get to create meaning for those objects that are usually so easily overlooked. By revealing their true personalities, we realize that they are a part of our own story, and profoundly. Each entry is a contribution to the underlying story of us.

The objects may, in themselves, have limits to what they can be, but they become diving boards to readers’ unlimited depths of triggered memories. We reflect on the relief of sitting in a chair after walking in bad shoes, feeling the prick of a thumbtack (a tiny trickle of blood squeezed from the thumb) before pushing it into a cork board, and the hours of clock watching in a cubicle or losing track of time and how it may have changed lives for the better (or possibly for the worst).

Each entry is a reflection of human consumption—sometimes restrained, other times gluttonous. The collection operates in different planes, some drawn from history and how other writers portrayed these objects before him. Stein wrote, “Rose is a rose is a rose.” It is a noun that is fine on its own—it doesn’t need to symbolize anything.

Kobylarz’s collection is a natural literary step in perception, even down to the titles of each vignette—one letter always capitalized: cockroacheS, thumbtackS, bowlinG. His collection attempts a democratic tone while teaching others how to trigger their own narratives, nodding to the predecessors who influenced his direct style.

For example, in Kobylarz’s vignette “sugar spoonS,” he writes, “hand-crafted to be licked even though it is thought of as impolite. If one is to measure one’s life in grains of sand, these are highly recommended. Actually, they are small devices, used as tiny mirrors of Morse code, to signal cohorts of the opposite sex that the dinner party in question is a bore and that there are lustier things to do.” Eliot would be proud.