Recently, I fell asleep in bed reading Porochista Khakpour’s new memoir Sick, the story of her lifetime of physical and mental health crises that eventually leads to a diagnosis of late-stage Lyme disease. In that sleep, I had a terrifying dream that my skin suddenly ripped open between my second and third ribs, and while the air leaked out of my body, I wasted time panicking about which jeans to wear to the hospital. In my waking life, I was wading through a bout of post-MFA anxiety the likes of which I’d never felt before, and I got a call from my older brother who told me he’d been bitten by a tick and diagnosed with Lyme disease (and successfully treated it with antibiotics) for the second time in two years. Everything, from the natural world to my nightmares, felt unreliable and all too parallel.

Similarly, to read Sick is to read a captivating story from a close family member whom you trust halfway. There is intimacy, care, and indulgence, but this book made me a wary reader. Wondering what could possibly go wrong next was often a tiring experience. It’s not that Khakpour isn’t engaging or that her story doesn’t deserve attention—it certainly does. But the nature of Khakpour’s existence is illness—she is constantly being hurt, getting sick, or being emotionally or physically tackled by the men who claim to love her, so much so that the experience of the book is one of walking on eggshells. As a reader, it’s difficult to be constantly bombarded by the catastrophe of illness. My sense of unease started with Khakpour’s traumatic car accident that opens the book, and maybe there’s a salient, if not too obvious, metaphor there. I wanted to believe that Khakpour and I were coasting along the road fine enough for the duration of our time together. I wanted to believe that we would indeed make it to our destination. But suddenly and always out of nowhere, Khakpour and I would be T-boned by yet another medical or personal malady.

I don’t say this to malign the book. While I certainly found it difficult to feel comfortable in the text because of this relentless jostling, I would argue that Khakpour’s insistence on including each one of these paralyzing details is one of the most compelling elements of Sick. When Khakpour gets an actual Lyme diagnosis from a medical doctor halfway through the book, she is told that she’d “taken enough antibiotics to be rid of it—whatever ‘it’ was,” and she is instructed to just get on with her life. But Khakpour, haunted by the memories of her previous iterations of illness, her descents into depression and anxiety, and all of the resulting personal turmoil, finds herself facing down yet another irreconcilable situation. She feels herself succumb. At this point in the book, all of Khakpour’s memories are the reader’s memories, too. We’ve watched her cycle through several painful disasters, and we feel the fear of those disasters—a true testament to this writer’s power. Because Khakpour doesn’t spare us any of her experiences, I felt some shred of what it would mean to be confronted by her fears and the reality of her illness once more.

“I couldn’t believe I was breaking down again,” Khakpour writes.

“Me either,” I said.

The magnitude of unlikeness in Khakpour’s narrative forces us to reckon with the amount of pain she must have felt as a human being. The fact that her narrative grows more unbelievably complex with time compounds the empathy we feel. The confusion between the medically dismissed “chronic” and the medically viable “late-stage” Lyme looms large in the background of this memoir—so much tension and disbelief swirl around each one of Khakpour’s medical interventions. Imagine living in the condition of this wake, how unsettling it must all have been. Sick doesn’t allow us to escape the consequences. It doesn’t allow us to forget that women and their emotions are still treated as hysterics and not reasonable reactors to intense pain. In that way, the memoir takes on something larger than the meaning of being a victim of late-stage Lyme. The memoir is about what it means and, more importantly, how it feels to live in a diagnosis-driven society with symptoms that deny diagnosis. Or, rather, symptoms whose diagnosis is denied.

That said, there are pitfalls to this narrative style. Khakpour admits in the acknowledgements that she had to do a lot of paring down to make the book work. There are already so many details, characters, and relationships, that to add in the “cultural criticism, historical anecdotes, facts, and figures” that Khakpour had initially included would muddy the content. We come to understand in this commentary that those things would likely drag the reader down, too. And while she cites Audre Lorde, Susan Sontag, Lucy Grealy, Virginia Woolf, and Anatole Broyard as the “gods” of the book, pinning herself to the literary tradition of the illness memoir as high art, there are moments when Khakpour’s prose breaks down in the service of streamlining.

Lines like, “A wedding meant little to me, and I had tried to convince Jacob that we needn’t do it legally, especially as the gay marriage debate was at a fever pitch in the national conversation, and I hate this inequality,” feel needlessly lengthy. This one in particular sags under the weight of the narrator's chatty self-characterization as an ally. Allyship and intersectionality are crucial things, to be sure, but the way the narrator's distaste for marriage inequality gets presented here feels like it's part of a checklist, not a deeply felt moral conviction. Despite my praise of the book’s ability to generate empathy, there are moments where we are expected to feel emotion alongside the narrator that doesn’t quite feel earned through the craft—places where the pacing is too quick or the analysis skirts too smoothly. At the end of page 139, Khakpour ends a paragraph about her loneliness and the alienation of her illness with the line, “Outside of me there were all sorts of possibility; it was the inside that was the problem.” I couldn’t help feeling that it was too easy of a turn. There were many moments like this where I wanted to be able to dispense with the breakneck pace of the storytelling to linger longer in these individual wounds.

The essayistic chapters “On Place,” “On Being a Bad Sick Person,” and “On Love Lost & Found” are critical to the book—they allow us to take a breath and process what’s happened on the journey—but they feel too limited in scope and quantity. I would have loved another thirty or so pages of emotional essaying, and I don’t see any reason why the book couldn’t support that. I trust that Khakpour and her wellspring of thoughtfulness could have easily handled the job. I would have liked to know, for example, how Khakpour did manage to handle her life as a writer and to publish as prodigiously as she did while all of this went on. The memoir disregards lengthier analytical thoughts on these kinds of issues in favor of the punch of Khakpour’s immediate feelings, but I found myself wanting both. If readers are asked to absorb so much unrelenting pain in a single narrative, we deserve to process that pain on the page with the writer. If the book was cropped in order to make it a more palatable read, editors should know that readers might sleep easier with a little more space to let Khakpour breathe.

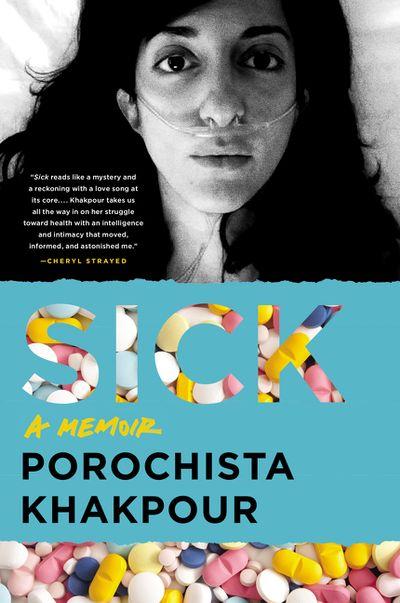

Sick

by Porochista Khakpour

Harper Perennial, June 2018

$15.99 softcover; ISBN: 9780062428738

272 pages