Tonight, I dreamt I was Nick Cave. When I woke, I thought if I wrote things down in his declarative, talk-singy way, I might sound a little like him, aping a nugget of his genius.

In the dream, I—Nick Cave—hadn't been sleeping well. I told you that in the dream. We had a long dinner table—interminable—draped in a big white linen, piled with a bounty picked from a verdant garden.

In the dream we had four children. They hunched over the long dinner table while I washed my Nick Cave hands. When I took a seat at the table the children straightened, then suddenly vanished as occupants of dreams often do, and it was just me and you. Susie Bick is Nick Cave's wife, but in the dream, you were not her. You were you, staring at me from across the table. That's when I told you I hadn't been sleeping well. That's when I told you I thought you were someone else. “Astaroth!” I chanted. Three times, as if demons work like Beetlejuice. In the dream you smirked, raised an eyebrow. “Well,” I told you, “just checking.”

The dream left me rattled. I lay here in the dark of our bedroom, the sound of a Q37 bus rumbling through our open window, you next to me, hopefully dreaming of something better.

I am not Nick Cave and I know you aren't the demons I accused you of being. The other day I listened to the last few tracks on Ghosteen, the 2019 Nick Cave & the Bad Seeds album. I whimpered as the title track thrummed through my headphones. “If I could move the night I would.” Cave's voice is a specter gliding through the song's ambient soundscape. “And I would turn the world around if I could / There's nothing wrong with loving something / You can't hold in your hand.”

Nick Cave's son died in 2015. A catastrophic accident which I refuse to recount because this is not about Nick Cave—not anymore. We lost a son, too—or a daughter. The biggest tragedy is how we will never know. We call her—him—them—Poppy. That's how big they were when we found out you were pregnant: the size of a poppy seed. An easy thing to terminate when it's a nameless ball of cells, harder when you give it an identity and carry it in your womb for ten weeks.

Poppy.

You told me the other night—before we jerked each other off in the same bed I write this in—that you felt sad about Poppy. I told you I knew.

“How?” you asked.

I said I could see it. “In your eyes. The way you carry yourself.”

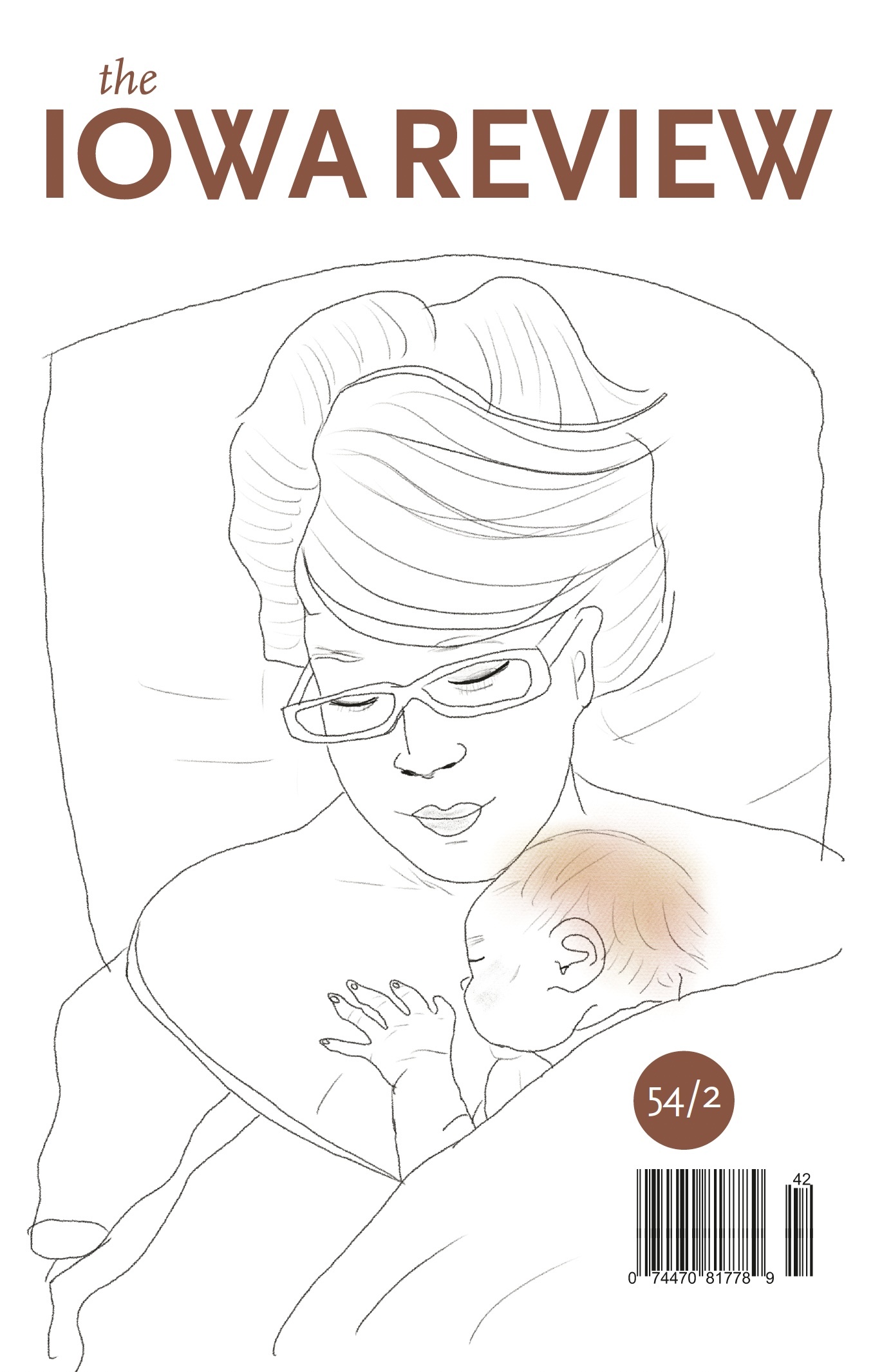

We're talking about trying again. We're talking about the risks and dangers we now know to expect. Clairvoyance brings a certain kind of wisdom but I'm still afraid to see you like that again. Retching until your body can do nothing but convulse. Confined to our sofa, our bed, back to the sofa, on and on. I whimpered listening to Ghosteen, picturing the new child we might create, the shape of their face and future interests. Cave rasped on: “You're sitting on the edge of the bed / Smoking and shaking your head / Well there's nothing wrong with loving things / That cannot even stand.”

I whimpered for that faceless child because they are not Poppy, and I miss Poppy. The child we never got to meet. I sat there, Nick Cave droning in my ear, and thought about how we wouldn't have to approach these conversations, live with these fears, if Poppy could have been ours.

Earlier in the album, on the fourth track “Night Raid,” Cave laments a passionate night with his wife in an old hotel, which ends in his twin sons being conceived. “They were just a sigh released from a dying star / They were runaway flakes of snow, yeah, I know / They annexed your insides in a late night raid.” By the time of Ghosteen's creation, one of those sons was gone. The anguish in this song is palpable. You gather Cave's appreciation for what these lustful scenes have yielded him—fatherhood and childhood—but his regret sears into you as well. “Night Raid” thrums with the beauty associated with passion and sex while offset by tragedy's painful foresight. Cave would not trade what that carnal evening gave him, but if somehow he had skirted it altogether, altered the course of history, maybe now he wouldn't have to marinate in the suffocation of loss.

There are few songs that have spoken directly to me as much as “Night Raid” has. How many times while you were sick and in pain, sobbing on our sofa over the decision to terminate or not, did I sit there with my hand on your back and wonder about the easier life we might have had if I’d turned down your advances the night we conceived Poppy? Even now, I replay that evening in my mind. All the sorrow we could have avoided had I told you I wasn't in the mood.

Truth is, I was in the mood. And so were you. We wanted to make a child. That's the most frustrating thing when I revisit that moment, knowing how much we wanted each other and how much we wanted a baby.

I let myself cry when you're not home or when you’re asleep like you are now. It's not that I'm keeping my sadness a secret—I've told you before how bad it hurts—but I've convinced myself it's your hurt that should take center stage. You are the mother. Your loss is greater, your pain unknowable. Maybe that's what I tell myself so I don’t fall apart in front of you like I did last week when you wrote that eulogy for Poppy on the hyperemesis website you visit so much. Poppy's dedication sitting atop hundreds more devoted to children unborn, all because of an awful sickness.

It's hard to look at you, sleeping like you are now, and not think of “Waiting For You,” the album's third track. This is the first song on Ghosteen where Cave really sings instead of talking over the music in his ominous baritone. He croons, “All through the night we drove / And the wind caught her hair / And we parked on the beach / In the cool evening air / Well, sometimes it's better not to say anything at all.”

The last line in the above verse strikes like a hammer. Ever since we lost Poppy, I've tried my best to stay strong in front of you, to fill you with comfort and encouragement any time you look remotely sad or despondent. And you've fired back at me with the same sentiment expressed in that verse: “You don't have to cheer me up. Sometimes I just want you to be here with me.”

As if to reassure me that this song is about you and I and no one else, Cave howls over his somber piano playing, “Your body is an anchor / Never asked to be free / Just want to stay in the business / Of making you happy.”

That's all I'm trying to do: cheer you up—take your mind off your pain. But in the end, I know this is something you must come out of in your own time and in your own way, new and different from who you once were.

It's impossible to believe Cave didn't compose “Waiting For You” with his wife, Susie, in mind. It feels as if he's singing directly to her, keening the song's eponymous chorus: “Well, I'm just waiting for you / Waiting for you.” With this song Cave gives you the sense he isn't weeping for his son or what he's lost, instead he's mourning for Susie and her insurmountable pain. He wants nothing more than to help his wife, to pull her from her grief like a lifeguard yanking a drowning woman from the ocean's punishing waves, but he knows he can't. Instead, he'll stay by her side, silently comforting her, waiting for her to return from her sorrow when she's ready.

Sometimes that's all you can do.

I find it remarkable how Cave went on creating in the wake of such debilitation. You can hear and feel heartbreak in these eleven songs—in Cave's wavering voice, his words, the atmospheric music. But beneath all that, if you dig through the pain, you discover catharsis and absolution. I suppose that's the power of good music. Like a cut that doesn't start aching until you can see it and study its shape and size, Nick Cave's songs allow me to see my wound for what it is, the circumference and diameter, the depth. And now it stings worse than before. But I wouldn't trade this pain. Oddly enough, it feels good to hurt, to grieve.

I wonder if these words read like a Nick Cave song. I suppose they read like me, for better or worse. Maybe it's not about how good it can sound. Maybe it's about sitting in a studio or on a bed in a two room Queens apartment, wrapped in your grief, composing something for the woman you love. The phone I type this on attempts to pull you out of sleep with its obnoxiously bright screen. I turn it further away from you, but you continue to toss and turn.

“Well, sleep now, sleep now,” Cave continues on “Waiting For You,” “Take as long as you need.”

What are you dreaming of? Who are you in your sleep?