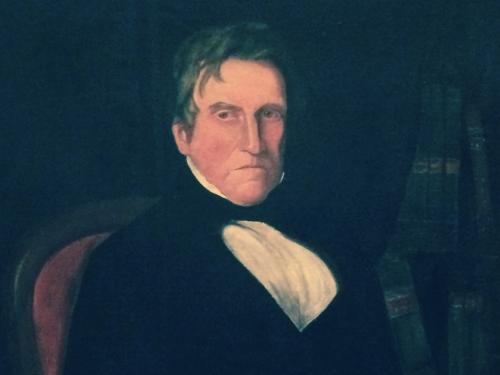

In 2012, a Long Island, New York conservator restores a 150-yearold oil portrait at the request of a local African American woman. The painting, passed down through her family, depicts her fourth great grandfather, William Dotson.

It’s good for you, my parents always said, when shipping me and my brother off to spend summers in rural Mississippi. We should never forget where we’d come from. My grandmother, Katie, and her husband, The Reverend, lived on a farm along a short stretch of Highway 18, an hour’s drive southwest from the state capital. Though each of their children had migrated north to attend college and work, my grandparents remained close to their roots in Claiborne County.

White-hot heat and thigh-high weeds, dirt-crusted vegetables, and a calendar of farm chores and church marked our Mississippi summers. All this, plus Sunday suppers at Granny Sarah’s, was good grounding, our parents believed, for privileged kids raised on air conditioning, integrated suburbs, and East Coast private schools. Sure, The Reverend was strict and humorless, holed up in his study most days preparing his weekly sermon. But he was a good and fair man, as worthy as Grandmommy Katie was witty and warm.

Both of my grandparents were born into families of former slaves. But each graduated from Alcorn College in 1937, a historically Black, land grant school on the outskirts of the county. Grandmommy Katie was a short doughy woman sculpted from solid bones. A patient schoolteacher once beloved by her students. The Reverend was a tall man, his back held ramrod straight, and devastatingly handsome. The Mississippi of my grandparents’ time was a state of more lynchings than anywhere else in the nation. Neither of them could vote until just a few years before I began visiting them on the farm. Yet, The Reverend had owned a shoe repair shop in Port Gibson and was a passionate civil rights activist. He was proud to have hosted Dr. King and his associates overnight once in his home when they passed through his state.

My mother says it was after her parents lost their third child and first son only weeks after his birth that The Reverend declared he’d been called to preach the Gospel. He ministered to several congregations around the state before returning to Claiborne County with his wife as the new Baptist preacher. The Reverend built a brick ranch on his wife’s family land within shouting distance of her two sisters. Aunt Wilhemina, who never married, cared for their ailing father in a dilapidated, wooden house on the hill. Their mother, my Great Granny Sarah, died before our visits began, but her house, having been passed down through her family, was where our family gathered. Aunt Etta lived near the one-room church The Reverend adopted as his own.

I hated the farm.

“Do I have to go?” I whined.

Rows and rows of cotton bolls and corn stalks fanned out endlessly on both sides of the highway. Time in town, more familiar terrain, was rare. If from the car windows, I snatched glimpses of chained Black men beside the highway, my questions often went unanswered. Unlike my younger brother and cousins, I couldn’t distract myself in tall weeds catching caterpillars and snakes. Chickens roaming the perimeter of Great Granny Sarah’s house or the feral cats living between its cement block foundation were cute, but the gnats that swarmed my sweaty hair and, kamikaze-style, dove into my nostrils always drove me back inside. I took refuge at Grandmommy Katie’s feet beside the sewing machine pedal, ordering fabric scraps for her quilts while she absently hummed Sunday hymnals.

I also hated my grandfather’s church.

Hot and stifling. Every single Sunday, I suffered. The Word, a fire-and-brimstone lecture lasting hours into the early afternoon. Someone singing off-key, while Aunt Wilhemina plucked out ol’ Negro spirituals on the piano. Weathered and hatted ladies, fanning themselves furiously to cool their spiritual engines, falling limp and glassy-eyed when the Holy Ghost took possession of their bodies. The Reverend’s religion felt overbearing. Indecipherable. Dull.

Most of the time I spent in Mississippi, I wished my parents had allowed me to stay home with them in Maryland. Though they both worked and I was forbidden from watching television or roaming the neighborhood after school, life was rarely boring. We attended church and Sunday school at home, too, but our Episcopal priest offered sedate sermons clocking in at less than fifteen minutes. An AME church we sometimes frequented had a three-piece band with a drummer! It was the late sixties and nearby, the nation’s capital was pulsating with anti-war activism, free-spirited love and religion, and the civil rights movement.

My father, a dead-ringer for blaxploitation movie hero Shaft, worked as an urban planner and community organizer in major cities along the Eastern Seaboard. I adored him. His prickly beard. The dark chocolate face that practically shone. “Come here and tell me what they’re teaching you in school,” he’d say and I’d proudly recite facts from a social studies lesson. But mostly, I adored the way Daddy took me into his confidence whenever he returned home having lobbied for new subsidized housing or health clinics. “It’s up to us,” he said, “to move our people forward.” Jews turned a dollar at least ten times amongst their own before it left their community. Whites, seven times. “Blacks,” and here he’d grimace, “only once!” The way he went on and on about the movement’s machinations as if I were his equal was mesmerizing. I was nine.

It was from our house on the city outskirts, in a tree-lined, quiet neighborhood we’d been among the first to integrate, that I learned about prejudice and pride. Once, two white classmates fell into step behind me on the walk home from third grade, giggling and chanting “Nigger.” That evening, as I cried in her embrace, Mom sniffled, too. Then, like many Black mothers before and afterwards, she warned me about life’s cruelties, prepping me for danger and death.

A different kind of talk shifted my attentions to pride. Conversations between my parents and those I overheard between Daddy and community leaders reminded me of our people’s power. The rallying cries of Birkenstocked hippies on our street affirmed it, as they slipped into a psychedelic Volkswagen minivan at the curb. I was still compliant then, absorbed by reefer smoke wafting from the van’s side gills. I was too young to understand the demonstrations raging downtown. But I sang along with James Brown, “Say It Loud, I’m Black and I’m Proud,” playing over the radio airwaves of The Chocolate City. I kept time with Soul Train dance hits on television, jerking my hips and popping my fingers.

But in Mississippi, The Reverend forbade dancing.

Daddy sported a dashiki in those years, and I, an oversized afro. When I wasn’t doing homework or chores, I read lots of books. We all did. Both Daddy and Mom were alums of elite, East Coast grad schools and skilled debaters, an attribute I admired then but less later when I blamed it for their marriage’s demise. Our dinner table conversations were a cross between a Harlem Renaissance salon with famous intelligentsia and a competitive game of tennis.

Revolution, Daddy argued, was a legitimate means to self-determination. Thwap! His cerebral arguments, both eloquent and long-winded, turned mere meals into marathon sessions of spirited one-upmanship. Mom, a research chemist who would become a gifted lawyer, held her own. Higher education and corporate influence Thwap! was the way to real change. Thwap, Thwap! I relished these verbal matches as a child especially since both Mom and Daddy encouraged me to play. Match point.

“What do you think?” they’d ask. “Assimilation or Africa?” And, I’d weigh in on the revolutionary tactics of the Black Panthers or Malcolm X. Game.

But in Mississippi, children were seen and not heard.

The Reverend cared little for my politics, my music or my hairstyle. Marcus Garvey’s boat back to Africa was ridiculous—my grandfather had all but broken his back earning a life for his family in America. According to him, the Devil inhabited young girls’ hips and most Motown singles. “I’m not studyin’ bout you,” he dismissed both me and my arguments. Similarly, his opinions on afros and self-love were unwavering.

“Why cha go and cut off all that pretty hair,” he grumbled once, looking at me with disdain. Before the afro, my mother had straightened my hair (initially with a hot comb, later with Revlon Relaxer, Mild) to wear loose around my shoulders or gathered into pigtails. My grandfather hated my new nappiness. As a man with good hair, it was beyond him why anyone would trade it for something else. Look what had happened to those four little Black girls only a few years before, minding their own business in a Birmingham church! Afros and self-love attracted unwanted attention, even death. In defiance of her father and in defense of my Black pride, my mother started wearing an afro wig in his presence. He hated my mother’s hair, too. It didn’t matter what anyone else thought.

In his house, The Reverend always had the last word.

The stupefying monotony of my childhood summers in Mississippi is broken by two especially vivid memories: the time I watched an older cousin chop a chicken’s head off for supper and run in circles behind the headless creature, and the day I ran into Great Granny Sarah’s house and froze in front of her bedroom wall.

Rendered in the style of those seen in venerable museums, the painting on my great grandmother’s bedroom wall was taller than I was and wider than my body plus two outstretched arms. Dark and formal, it hung centered at the head of her bed. The man’s eyes were flat. Ice-blue. His gaze was menacing. I couldn’t stop staring at the beak-like nose and paleknuckled fingers shaped like talons. Or, the beady eyes that followed me no matter where I shuffled in the room.

But who was this guy? And why was he hanging on our wall? Daddy and I favored brown Jesuses and framed African prints. We admired men like Martin and Malcolm, not old white men in poofy shirts.

“Wha’cha doin’ child?”

I’d been so riveted, I hadn’t noticed my Aunt Wilhemina.

“Nothing.”

“Then why ain’t you outdoors?” she demanded.

Shifting my weight nervously, I stole a glance at the dirt through a missing floorboard between my feet. I should have known not to leave Grandmommy Katie’s side. I swallowed hard.

“I’m just looking at that man.”

Aunt Wilhemina cackled. Turning her back to me, she strode back towards the kitchen. What I heard of her rebuke was confusing and cold.

“Ha! That’s your kin.”

Census documents in Claiborne County, Mississippi record William Dotson’s birth date as 3 September 1794 and the date of his death as 2 May 1858. Dotson is listed as white, a farmer, and the owner of twenty-eight slaves at his death. His marriage to Mary Jane Bryce, who died young, bore him no children. But, at fifty-six years of age, he fathered at least two children and a line of descendants with his mulatto slave, Winnie Jones.

More than once, Mom told me how growing up in Mississippi, she was teased by other kids in school. “Hey, Lo-ret-ta,” they’d jeer, spitting out syllables with uppity fanfare for emphasis. “Hey you! Banana Skin!” The children singled her out because of her almond-shaped eyes and vanilla coloring, though middle school chubbiness probably also made her a target. Segregation ensured that every one of Mom’s classmates was brown and none were white.

“Banana Skin, Banana Skin,” the darker-skinned kids taunted in unison. Then, Chinkman and Light-Bright-and-almost-White.

It was painful for her. And it made no sense given prevailing definitions of race—that only one drop of Black blood made a person a part of our besieged minority. Besides, fair skin had never protected Mom and her family from whites’ hatred. The KKK, who’d threatened The Reverend by name in local newsletters, didn’t give one hoot about their skin coloring. Neither had the carload of white men with shotguns at the crest of a single-lane bridge, the ones who’d demanded her daddy reverse his car to allow them to pass first. Mom buried her head in novels and books of poetry to escape. Sometimes, she fell into her mother’s arms, teary.

“Hush, child,” her mother soothed. “They’re just jealous of your book-smarts,” she said of her schoolmates, “or your manners.” Then, she’d sigh. “Lord knows, we got enough holding us back. Why colored folks hurt their own is beyond me …” she added, her voice trailing off.

When she was only sixteen, still shy and sheltered, my mother and her family drove from Mississippi to college and she left the South for good. Mom had been accepted at Howard University, a historically Black institution in Washington, DC, boasting the best and brightest of her community. The day she traveled north, she carried her own packed lunch in case they were forbidden to purchase food or use the bathrooms in restaurants along the way. The day Mom graduated, she packed a suitcase for a chemistry fellowship in Europe, her first job in a research lab to follow. The flight to Zurich would be her first airplane ride.

Howard was a Crayola box of brown skin tones. Smart students by the dozens. Boys galore. “Oh my God,” the young men called out to Mom as she walked up The Hill and across campus to classes. “You hurtin’ me,” one would say, his buddies whistling at the same time. Black and white photos from those days depict a beautiful young woman who’d lost her baby fat and adopted the grace of fifties movie stars like Dorothy Dandridge and Grace Kelly.

It was fairer-skinned girls like Mom who were considered the prettiest. She was elected the Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity’s Sweetheart and the university’s Homecoming Queen, enjoying lots of attention from eager suitors. But it made Mom angry when her coloring afforded her special notice. She never felt any arrogance or superiority because of it; instead, it shamed her.

Eventually Mom met my father, a student in the School of Architecture. Mom said Daddy was intense and passionate, very smart, maybe even a little dangerous. Something strong and enduring reflected back at her from the blue-black of his skin. When folks teased her about him, Mom parroted a popular catchphrase, “The darker the berry, the sweeter the juice!” When my father and his cousin drove across four segregated states, disregarding the dark and the reek of rancid sweat beneath their armpits to ask The Reverend for Mom’s hand, that had sealed the deal.

Mom always told us she married the darkest man she could. Perhaps like another of our ancestors, she was securing her children’s place in their community. “So no children of mine,” she said, “would ever suffer my humiliation and rejection.”

At his birth in 1850, William and Winnie’s son was gifted with his father’s fair skin coloring. A small black and white photo, circa 1900, of Henry Dotson standing before an exterior clapboard wall still survives. Henry gazes into the camera directly but not unkindly. He wears a formal coat jacket and vest over a white round-collared shirt, and he stands, his back straight, the way a free man might have.

Claiborne County census records record Henry Dotson as one-fourth Negro or a quadroon (Q), and a farmer with no mention of slaves or sharecroppers at his death. Records attest to his marriage to Angeline Walters, a Black (B), on 28 February 1870, and his fathering of thirteen children with her. In the 1910 census, the last one before his death, Henry’s household is said to include his mother, Winnie, and several half-brothers and sisters. Before his death in 1918, he is said to have amassed a total of 751 acres of land.

I leaned in, not wanting to miss any of Grandmommy Katie’s story.

Over the years, I’d asked her many questions about Dotson and his portrait. How had it come into her possession? What had happened to the family Bible with the births and deaths of relatives scribbled on its first page, the one she traded to her sister for the painting? I also wondered about the man. Why had she protected his memory? Had Dotson wept at his wife’s death and, only afterwards, longed for female company? Had he whipped his slaves to tame them? I wondered if Dotson and Winnie, especially Winnie, bedded the other with any fondness and pleasure. Had Dotson acknowledged the son Winnie bore him as his own?

But Grandmommy Katie had few answers and now she was ninety-two and living in a nursing home. Whenever I came home to Maryland, I made a point of visiting her. I was in my forties and married by then, with three children. Not every visit was satisfying but occasionally, my grandmother recounted details from her life. One day, she remembered a visit she and her elder brother, Ernie, had taken to their Grandpa Henry Dotson’s house with their mama, my Great Granny Sarah. A quick calculation set this memory at about 1919. Grandmommy Katie couldn’t have been more than seven years old at the time.

Ernie said everybody knew who their Grandpa Henry’s papa was.

“Everybody?” Katie asked him.

“Well, everybody ’round here,” Ernie had said. He paused for dramatic effect. Grandpa Henry was Master William Dotson’s son. “The folks in Port Gibson whisper about it—his papa, I mean. Some people further away spread talk, too. But no one pays them any mind.”

Ernie, Katie, and their mama were traveling by buggy. Though only fourteen, Ernie held the reins and steered. Their mother, Sarah, sat in the rear seat, leaving Katie a spot up front as a treat. I imagined the buggy’s wheels catching every pit in the dirt road and a swayback horse neighing in complaint.

Playfully, Grandmommy Katie mimicked her younger self for me.

How she’d crossed her skinny arms across her chest—so what?—and puffed it out in a show of maturity even though she really hadn’t understood my great, great grandfather’s secret at all. All Katie knew was that she adored her Grandpa Henry. He favored their mama and, by extension, was always kind and gentle with them. On Katie’s last visit to his house, he’d given her two books for her homeschooling and some hard, striped candies to suck on.

“Grandpa Henry ain’t tryin’ to be anything he’s not,” Ernie continued, “… just because of Master Dotson.” Her brother was really carrying on. “He’s not tryin’ to pass like his sister,” Ernie told Katie. Grandpa Henry had even married Miss Angeline, a woman Ernie claimed was “dark as tree bark!”

Katie was confused. “What’s that mean? What’s pass mean?”

That’s when their mother had leaned forward and smacked Ernie on the back of his head. “Mind your manners,” she’d scolded. “Now hush!” She and Ernie had to sit the remainder of the buggy ride in silence.

What happened next, I wanted to know.

On their way home, Grandmommy claimed she hadn’t been able to stop asking questions. As a child, she’d always been scared of night clouds, the way they closed in over the fields and birthed monstrous things in the trees and low scrub at either side of the road. The buggy still had to pass by the family cemetery behind the church.

“Mama, is Miss Winnie a slave?”

“Mama, who does Winnie belong to?”

“Why is Grandpa Henry so light and most of his brothers and sisters so dark?”

I’d seen that cemetery on my last visit to the farm for The Reverend’s funeral. How overgrown with weeds it was by then, full of toppled headstones. With the death and departure of each descendent, Great Granny Sarah’s house and surroundings had become a rotted shell of its former self. I remembered how from the funeral hearse, I’d looked out over Mississippi’s cotton, ruptured and ready for picking, salting the fields for as far as my eyes could see. A mother’s talk, I thought now, would have been calming to a child in that place.

“Mama, who is Miss Winnie married to?” Katie pressed her mother. That’s when Great Granny Sarah pursed her lips like she didn’t want to talk. Grandmommy Katie said she knew that look so she’d swung back around in the buggy fast to stare straight ahead to the dirt road in front. She didn’t want to watch her mama get angry.

“Nobody,” her mother had sighed. She paused. “Your Uncle Billy and them’s daddy was a slave just like Miss Winnie. Slaves were married in their hearts, not by the law.”

“Colored folks and slave masters never married,” Ernie chimed in.

I sucked my teeth, interrupting Grandmommy Katie’s story. “So Master Dotson raped Winnie.”

My grandmother’s focus strayed to some faraway place beyond my face.

“Oh, I don’t know, Child,” she sighed. “Winnie gave her children an easier way.”

Back in New York, on a bleak and wintery day between school drop-off and pick-up, I loaded the carefully wrapped canvas into the back of our family Suburban. I was enjoying a comfortable married and family life. But disturbing run-ins on race had pushed me to learn more about myself and my family history.

Unwanted by my mother, the Dotson portrait had sat in my attic for almost a decade behind boxes of pregnancy clothes and office keepsakes, wedged between elementary school science projects on foam core. Material reminders of slavery’s shame and horror demand safe boundaries like set visiting hours, guided tours, or exhibits behind glass. But time was running out on my 101-year-old grandmother. I couldn’t imagine why but she pressed me repeatedly, “When you gonna fix my painting?”

Carole was the friend of a neighbor and an art dealer with connections.

“Wow,” she sighed as she unwrapped the painting, flakes of paint the size of quarters flying off in every direction. “It’s in pretty poor condition,” Carole said by way of warning. “To restore it will require significant time and money.” Who is he, she wanted to know.

William Dotson is occasionally recorded in documents as Dodson. His birth certificate lists him as a Dodson but his father’s tombstone bears the inscription, “Erected by his son, William Dotson.” A published history of the Dodson / Dotson family records William’s father as Esau Dodson, a veteran of the Revolutionary War. Four generations before him, John Dodson, who is also a relative, was a compatriot of Captain John Smith, the English soldier and explorer. Together, Dodson and Smith are credited with the first permanent settlement in The New World—Jamestown, Virginia in 1607.

While it was fascinating family folklore that Henry Dotson was a mulatto and his father, William Dotson, a white plantation owner, it was hardly revolutionary to how I saw myself in the world. I was Black, I contended. Not black with a lower-case b. Or, brown. Definitely not Negro or Colored. I was unapologetically Black.

But my husband wasn’t. And, neither were our biracial children.

Zubaid and I met in our first job after college in New York City and flirted throughout a grad school stint together at Harvard Business School. It was the 1980s. We fell for one another quickly, spellbound by his family’s forbidden love, Manhattan’s lights and energy, and Wall Street excess. How charmed I was by my tall and handsome suitor, a Pakistani Muslim, and his magic carpet ride to some exotic happily-ever-after. His drive was a puzzle piece to mine; his intellect, a match for my father’s.

It’s difficult to admit to my obsession, or what might have been his. But in imagining our future family, I must have sided with my mother on the optimal path to our people’s advancement. The fact was, in spite of my father’s politics and preference for street corners over corporate boardrooms, I’d grown up in a predominantly white neighborhood, school, and church. My parents’ abhorrence for elitism meant I rarely socialized in Black youth organizations like Jack and Jill of America. In college, I would have had to travel to other campuses to join a Black sorority and I didn’t bother. By the time my children with Zubaid were born, we would be neither Black nor Pakistani, but Global Citizens with uncompromised possibilities.

Over time though, marriage to a man of another ethnicity raised uncomfortable questions. Being strong willed, I’d refused before I wed to be bullied or reverse-psychologized into sacrificing my personal happiness and will. My authentic self said I loved my husband. But increasingly, I wondered what part colorism, my people’s secret shame, had played in moving me to marry outside my tribe. Was a loss of face or imposter syndrome turning me short-tempered and skittish like a fugitive? My husband and I are both minorities. He and I share the same brown skin. Yet, our sameness couldn’t rescue us from cultural blindness, the assaults we lobbed at one another whenever our instincts for survival felt threatened. Dotson’s portrait and my ancestry were a reminder to resist any attempt at my diminution.

A few weeks before my fiftieth birthday, when clinging for dear life to Feisty and Fabulous, I boldly changed my hair style. Cutting the long, straight hair my stylist and I had maintained for years, I asked for an edgy boy cut instead. Wet or air-dried, it became naturally curly like an afro. Zubaid was furious but indirect.

“What’s the matter with the way you’ve always worn it?”

“It’s too much work,” I explained, referring to the time-sucking, expensive relaxers (still Revlon, Mild) I endured.

“Just sweep it up into a bun,” he insisted. Like our daughter did when it rained? My hair didn’t sweep. Water welled behind my bottom lids.

Why hadn’t I asked for his opinion beforehand, he pressed.

“Because it’s mine,” I shot back.

I felt it immediately and it stung. Those age-old notions of beauty, and distancing from too much Blackness. That feeling of otherness. Tears ran down my cheeks and pooled like stagnant water in that soft indentation between my collarbones.

Deposited deep in the physical body, a family’s stories metastasize as identity. Since childhood, mine had morphed and multiplied. I was more Black than I’d admitted. That sense of self kept seeping from my memories, from slits in the past right before new nappy afros and right behind icy rebukes ’bout kin. Identity was oozing from old wounds and, now, broken skin scabs.

Carole checked in with me frequently. I was grateful because all I had was a handwritten receipt and our signatures on personal notepaper. Suppose it were valuable and I never saw the painting again? Would Carole’s expert—the man re-stretching the canvas to protect it from further damage, cleaning its grimy surface, and painstakingly applying new paint—enhance or destroy its value?

“This could be a historically important piece,” Carole allowed.

Of course, it was. I considered joking about my ancestry, that as a descendent of our Founding Fathers, I qualified for membership in the DAR (Daughters of the American Revolution). But I didn’t. I was too proud.

It would be several months before the restorer’s work cast a new patina on Dotson. The top hat Dotson holds on his lap came into focus, that, and a cane he grasps with arthritic fingers, not prey. His lips, pursed in reproach or perhaps sunken from years of gum decay, are evident in the new light. Painted only six years before his death, the portrait depicts a sober man of fifty-six years in less-than-stellar health. Several weeks later, the restoration revealed the red velvet chair on which Dotson sits; his bulk, indicative of, perhaps, less-than-abstemious habits; leather-bound books in the background, of more learned men than he; even Dotson’s intellectuality, the confusing mix of stoicism and reproach. One abomination after another.

Eventually, Carole called me with important news.

“We’ve uncovered the artist’s signature.”

I held my breath.

“It says T.C. Healy,” she reported. “1853.”

An internet search reveals Thomas Cantwell (T.C.) Healy was a portrait painter and the younger brother of prolific artist and Unionist George Healy. George’s commissions include Queen Elizabeth, King Louis Philippe, Lincoln, Grant, Adams, Jackson, and Clay, and his portraits hang in the White House, Versailles, the Smithsonian, and the Corcoran Gallery. Thomas’s legendary drinking and womanizing, plus his Confederate sympathies, place him on the wrong side of the Civil War, fame, and fortune.

It is sad, pitiful really, how the ghost of a man and an old painting so utterly undid me. But there is so much complexity to racial identity, especially across generations. So many expectations to manage when we intermarry. So many assumptions to thwart. So many layers of hurt to heal.

I cannot deny I enjoyed many comforts: our house in the suburbs, the children’s private schools, exotic international holidays. I was privileged with access to influential jobs, meaningful political and charitable causes, and fancy clubs. But my Black friends were dwindling and access to my community was harder to come by. I rarely stepped foot in a Black church except for a funeral and yet with time, I’d come to value my family’s deep faith. That our children had failed to inherit any spiritual literacy from either me or Zubaid made this loss more painful. It was disturbingly hard to muster enthusiasm at home for political causes or popular films relevant to my community. Even the deep friendships I’d hoped for for our children in joining Jack and Jill never materialized. Secretly, I wished at least one of them were smitten with someone Black but how dare I say so when I’d fallen in love with their father?

Never forget where you come from, the elders had always said. But I had. I was estranged. Worse, I felt like a traitor.

Here, let me say that Zubaid experienced sacrifice and loss, too. Many of his family stories also went untold, his family’s ways, unobserved. We simply hadn’t understood one another’s fears when we married or known their pull. Like the discomfort Zubaid felt when I openly celebrated brown Barbie dolls and heroes in literature, sports, and media. His community had succeeded in America by keeping their heads down and working hard, not by making waves. Then, there was my resistance to moving to Greenwich, Connecticut where more homogeneous was code for affluent and Caucasian (with a sprinkling of Asian). Privilege may have insulated our toddlers, but I knew it wouldn’t protect teenagers in hoodies if cops pulled them over in their cars. There was Zubaid’s knee-jerk disdain for hip-hop and baseball caps worn backwards. And mine, once, to giving our children Muslim names. (What mother in good conscience brands her brown-skinned children with not one but two strikes against them?)

Birthing biracial babies and raising well-adjusted young adults is delicate, difficult work. It left us as parents, wounded, like fugitives to some and strangers to many. The restoration of the Dotson painting amounted to delicate, difficult work for me, too.

Initially, I had beat myself up for repairing the portrait at all. I was well beyond acknowledging the man; I was memorializing him by bringing new life and light to his portrait. Later, I accepted that maybe I’d disavowed the multiple stories of my Blackness just to remind and warn myself about our nation’s bigotry. So that I never let my guard down, like my father always urged.

Once defensive with my family, weepy and angry for all I hadn’t been able to convey about race, I turned quietly insistent. Rather than muzzling myself in the face of racial tropes or ignorance, I continued to educate and convert them. Rather than giving up in frustration when my warnings about systemic bias left our teens blank-faced and dismissive, I repeated myself. Then, after weeks of nationwide protests in 2020, on the heels of countless Blacks harassed, brutalized, and murdered by police, our family conversations on race and identity finally changed. My husband grew outspoken with friends and work colleagues. His kids were “Black too,” he announced; they were accomplished and capable yet likely to be discriminated against just like Floyd because of their skin coloring. Our twenty-somethings steeped themselves in activists’ charges and publicly advocated for equity and justice. Vindicated and relieved, I felt restored by these affirmations.

Claiborne County records include William Dotson’s will. Dated 21 January 1858, the will appears to have been crafted to sidestep the period’s social and legal constraints forbidding slaves to legally inherit property. It divides Dotson’s estate, his twenty-eight slaves, between his siblings and their children and, having had no wife or legitimate heirs, the remainder of his property “without condition” to his mulatto children with Winnie. For fear of legal retaliation, Dotson does not name his mulatto children in his will.

The “without condition” clause prevented Dotson’s siblings from contesting it without sacrificing their shares in his estate. Indeed, Dotson’s sister and brother-in-law, Elizabeth and Richard G. Smith, filed suit and contested his will in 1859 on behalf of the family, but years later, the complaint was dismissed in favor of Dotson’s executor, Lemuel N. Baldwin. The plaintiffs received nothing.

Court documents suggest that on 1 January 1870, Baldwin deeded 1400 acres of land and two plantations to Dotson’s overseer, J.I.B. Rundell, who on the very same day deeded two hundred acres to Henry Dotson and Winnie Jones. It is Baldwin, according to court settlement documents, who advanced the five hundred dollars in cash to Dotson and Jones for the purchase. In 1878, Rundell deeded the same amount of acreage to Sarah, Henry’s sister, and in 1878, he sold the remaining acreage back to Baldwin for the original purchase price.

Without written documentation of the exact nature of William Dotson’s relationship with his slave-born children, my ancestors were left to interpret the circumstances of his life on their own. Great Granny Sarah and Grandmommy Katie may have decided that good and evil, and sin and virtue, exist in everyone. That each must be weighed against the other to determine a man’s worth. Small and human details woven through the fabric of my family history and captured in a family heirloom had complicated the institution of slavery, leaving it full of contradictions and innuendo.

Once it was back in my possession, I paraded the restored and newly framed Dotson painting back and forth at the nursing home. I struggled to hold the heavy piece between my outstretched arms and to watch my grandmother’s face at the same time. Though she’d turned 105 and her eyes were milky, she beamed at me. Even my mother’s eyes softened.

A single painting had bent and distorted history, refracting multiple truths, not just one, like a prism. Dotson was a slaveholder but his actions had gifted his descendants a legacy of social activism and fostered our land holdings and literacy. I was unapologetically Black but had many selves—ones I could no more hide in an attic than ignore in mothering my multicultural children. Perhaps this is the cognitive dissonance my immigrant husband feels as a proud Pakistani and a first-generation American. Perhaps this is the reality my biracial children were born to protect. Two truths can exist at same time.

My children weren’t especially interested in Dotson. I get it. It was only in my middle years that I’d become interested in old things and old people. But I herded them together that day anyway with their great grandmother. I wanted them to witness Winnie’s agency—how sheer guts and determination had allowed a slave woman to dream big for her children’s future. How each of us was the product of seized opportunities and choices, stolen joy where we could find it, and a dedication to something bigger than ourselves. One day, I hoped they’d ask questions like I had. That like Granny Sarah and Grandmommy Katie, they’d treasure their ancestry and pass it down. And that, like Henry Dotson and my mother, they’d heartily embrace their Blackness. But I must leave them to their own journey.

We’ve come to a truce, Dotson and I.

I had planned to donate my painting to a museum or university collection but years later he’s still with me. I can’t hang the old man in my home. He’s still a slaveowner. I’m still Black. Instead, Dotson sits on my bare, hardwood floors propped against the wall, stone still and silent. Where once he sucked all the air from a room while descendants cowered, now there is nothing. An untortured and uncompromised nothing. Occasionally, I stare at him from the opposite side of the room. I marvel at the restorer’s work—how whole patches of paint missing from Dotson’s face have been filled in. I am both ashamed by and grateful for him.