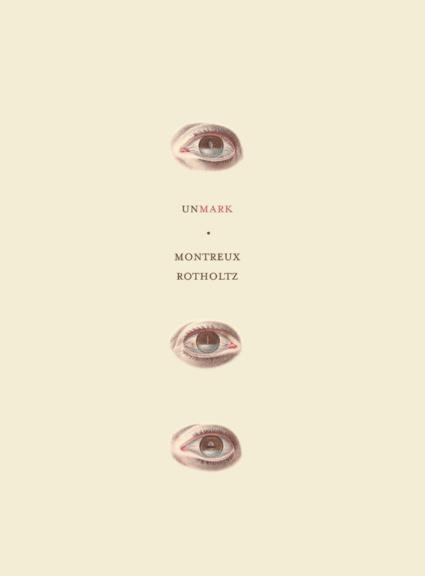

Montreux Rotholtz’s debut poetry collection, Unmark, is puzzling, and like all good puzzles, it challenges the puzzler to slow down and take a hard look. To pluck out a corner from a pile of pieces and lay down an edge. I’m reminded of Mary Szybist’s abecedarian “Girls Overheard While Assembling a Puzzle,” which begins: “Are you sure this blue is the same as the / blue over there?” Unmark asks this question again and again, as Rotholtz probes the connotative and emotional power of the given gestures and objects. Under her discerning floodlight, nothing is sanctified or pure—not girlhood, not beauty, not landscape, not dogma: “Blight of crop / becomes blight of fields becomes just blight.”

Perhaps Szybist, who selected Unmark as the winner of the Burnside Review Press Book Award in 2015, was also drawn to Rotholtz’s quandaries about imperfection. Not the phony, inner-beauty kind that are touted by soap and underwear commercials, but the real deal: a female experience characterized by unnavigable mazes, gruesome violences, and standards so elusive they’re hilarious. This contrariness is Rotholtz’s genius. In an attempt to fulfill their own prophecy—to unmark, to wipe clean, to begin again—the poems push against each other like crowding teeth. The flaws that Rotholtz navigates are bodied, lived, and witnessed: “a piece of your thigh taken / out by frost”; “the leper’s arm that thrust /through the wall of falling cream”; “Mother in her hair net / and ice skates.”

Like Szybist’s poem, where two young women are assembling an image of Mary’s annunciation (i.e., literally assembling their own damnation, and delighting in it), Unmark speaks to inherited religious shame, self-annihilation of the female ego, and purity—that pressure cooker. Each poem introduces different spills and different solvents—an ink jet, a zit, a tripping, a scab—and ultimately, each leaves a different stain: “Sugared be the beet, the red ant, / the spiked border”; “the holly smoke / the burnt protein / the bitter pellet”; “the kind of woman / who looks naked / all the time.” But ultimately—brilliantly—the poems meet neither their marks nor their makers. Instead, the poet caves to the necessary utterance, to the black stroke on the clean page. Failure is the greatest success of Unmark because it doesn’t unmark its reader at all. It imprints. Spills the beans. It doesn’t forgive us.

The poems have a quality of completeness that demonstrates Rotholtz’s desire to divine wholeness from a sum of parts. They are deftly, intellectually made objects. There’s prosody, surprise, and a vocabulary that had me examining the third and fourth definitions of words (“albumen,” “dentures,” “fisk,” “whelk”). Rotholtz’s poems want to confess, baptize, purify, but these attempts come up short. Although she accepts the impossibility of this task from the moment the book starts—“Lord, I was made / irradiated—”—she doesn’t stop reaching for the golden ring of it. A struggle for sublimity characterizes this collection, and although sublimity eludes her, it is Rotholtz’s fight—her teeth, her claws, her doubling back—that gives the collection its foothold.

Her wordplay is particularly vibrant. There are eleven instances of the word “just” in this collection, and each rings with multiple definitions. The whole Liberty Bell of justice up against the meager adverb: Just, barely, simply, only so. Up against a qualifier of exactitude: utterly, absolutely, just so. “Just once / have I been a rictus”; “They were just property”; “Just think of me as a pillar of light.” The word “just” characterizes the book in a new way each time it is used, making the notion of “justice” a shifting, amorphous thing. There is a reach for justice in Rotholtz’s poetry, for a world that makes logical and emotional sense, that honors the beauty of precision, that doesn’t expect too much or too little. However, this standard of perfection goes unmet, as it must. What’s left is reality—just in place of justice—and these poems do the hard work of making do.

I am especially struck by the poems written horizontally in prose sections. These exhale from the tightly wound syntax and wordplay of Rotholtz’s other poems and allow for them to speak in unbroken sentence units: “We went to sleep in the power plant and were awakened some time in the night. There was a dog noise. My husband opened his good eye.” If the other poems in the collection do the work of the microscope, zooming in and zooming in with lens precision, these prose poems do the work of the microfiche machine that appears earlier in the book: “In the archive an avalanche / is permanently sliding, angled, into a ski lodge.” These prose poems are panoramic and uncouth. To boot, the reader must turn the book on its side to read them. It's an inconvenient and silly gesture that rings with deadly seriousness, and I love Rotholtz for it.

Instead of falling back on the standard Madonna–whore complex that situates women between two mutually exclusive extremes, Rotholtz invites both women to breakfast, serves them orange juice in coffee mugs, and asks: what gives? Giving denotes the central question of Rotholtz’s poetry. The giving of life, the giving of body and voice, the givens of womanhood—and of course, the taking away. I felt convalescent when I read this book, like I had survived a dangerous procedure. The drama having passed, I had to move on, eat my hospital Jell-O, and face the coming day. Yet, what Unmark took from me was fear of hopelessness. It is not healing, so to speak, but it accepts the severance, the split, the fracture, the catastrophe. It celebrates it. “Help me I’m partial,” she pleads in a poem fittingly titled “Psalm.” I’m afraid I can’t, because I am too.

Unmark

Montreux Rotholtz

Burnside Review, 2017

$13, softcover; ISBN: 978-0999264904

79 pages