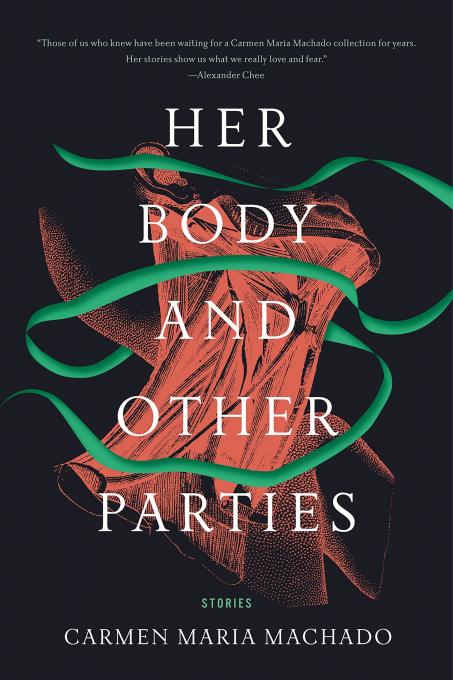

Carmen Maria Machado is the author of the acclaimed debut collection Her Body and Other Parties, a finalist for the National Book Award. Her stories have appeared in wide-ranging publications, including The New Yorker, Guernica, Granta, Best American Science Fiction and Horror, and VICE. A graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and the Clarion Science Fiction and Fantasy Workshop, Machado makes real a boundary-breaking assortment of extreme or extra-realist situations, like disappearing women stitched into formal gowns or dead girls and doppelgangers haunting Law & Order: SVU’s Detectives Benson and Stabler. Within these fantastical landscapes, Machado grounds her narrators, and thus her readers, in visceral emotion and human contact. Her work speaks to the dangers of baring oneself, to the strength and the vulnerability of our flesh, to the lusciousness of our physicality, and to the possibilities of the body as a place of refuge. Her Body and Other Parties lives up to its title, presenting to us a range of women giving and consuming and grappling with intimacy. I sat down with Carmen at Cortado Café in downtown Iowa City on November 3 and asked her some questions about her National Book Award short-listing, her thoughts on genre and working between genres, and her upcoming projects.

The following interview is edited and condensed for clarity.

Katlyn Williams: Welcome back to Iowa City! How does it feel?

Carmen Maria Machado: I’m really excited to be back. I love Iowa City, and I miss it tremendously. It feels so familiar to me. I went to Prairie Lights earlier today and saw my little display on the table in the front and thought Wow. I went to so many readings there, and now I get to go as a writer. I miss something about Iowa City, the contained-ness of it. There’s something about it that I find very soothing, so it’s good to be back.

KW: We’re lucky to have you. Congratulations on the National Book Award short-listing! How did you celebrate?

CMM: The longlist was weird, because I didn’t know ahead of time. So, I was actually on a train back to Philly from something I was doing in New York, and I’d already scheduled a massage because traveling kills my back. So I was on the train, got the news, was like [excited noises], and thought, “OK, I guess I’ll go get a massage now.” And then I checked out for a few hours. And then for the shortlist, I got properly drunk. My wife and I went to this restaurant in Philly that’s in an old bank where the waiters wear little white coats, and it’s sort of this 1950s steakhouse. They have really great martinis. So we get martinis and escargot, and it’s my favorite little treat if we celebrate anything. Which is a lot these days! Sometimes we just pop little bottles of champagne at home, but for this one, it was like, “No, we’re going all out.”

KW: Sounds perfect. I’m sure you’re asked to talk about genre frequently, but I’m fascinated by your simultaneous commitment to publishing in different arenas, both lit magazines and genre. It’s sort of rare to see someone consistently doing both. Is this something that’s important to you?

CMM: Yeah, I publish in different magazines that do seem to belong to distinct sort of “tracks”: the Clarion Science Fiction and Fantasy Workshop and Nebula/Asimov Awards track, and then the National Book Award, MFA program, and say, New Yorker track. So the work itself isn’t different, but I do try to go back and forth with whom I submit to. It’s nice to keep my foot in both communities; it’s important to me that I do both. And the neat thing about the genre community is that so much of their work is online, and there are really good magazines, so you get a lot of readers that way. But my work doesn’t change between a genre magazine or a lit magazine; it’s all the same amalgamation of liminal fantasy/horror stuff with a literary sensibility.

KW: Do you think it’s important for you to do both partially because of what you consume, as well?

CMM: In terms of what I read, yes. When I came to Iowa, I was truly dreadful. I had certain prose instincts towards stoic, realist stories, like what I imagined I should be writing, but I wasn’t good at that genre. My classmates were very kind but also let me know that it wasn’t great. But they would say “this part of it is great,” and it would be this fabulist layer in the corner. Then I started reading George Saunders, Kelly Link, Karen Russell, and others, and my brain began expanding, and that’s where my style, or what I think of now as my style, came together and took over. So, yes, what I was reading was definitely reflected in the work. When I was reading, I thought, “Oh wow, I didn’t know you could do this.” That’s the best feeling in the world, where you think, “I want to do this—not exactly this, but something like this.”

KW: I love the narrator in “The Husband Stitch” because she’s so self-aware, and she knows what kind of story she’s in.

CMM: Yeah, it’s like the opposite of genre blindness. Like in a zombie movie where they haven’t seen a zombie movie; this is the opposite.

KW: Was it important to you that her experiences as a housewife be structured through the lens of other stories, specifically in this case, urban legends?

CMM: It’s weird admitting it, but that story came together through three different projects. I wanted to write a story about a mid-century housewife who enjoys sex, and then I also wanted to do a retelling of the girl with the green ribbon story—something I wanted to do even while I was in Iowa, though I wrote it later—and I also wanted to write about urban legends, like “Bloody Mary.” I also had a title—“The Husband Stitch”—that I’d thought of, but it wasn’t at the time connected to those ideas. So when I sat down, I realized all these pieces could come together. So I sort of backed into it, which is what a lot of writing is, clawing your way slowly toward the whole thing.

KW: You mentioned wanting to represent a housewife’s sexual desires, and your collection overall is super sexy. I love that about it, and I think it’s pretty rare in fiction to see women’s sex lives shown in such matter-of-fact detail. How did you think about the project in terms of representing sex and love?

CMM: I’m really interested in sex writing, and I feel like it’s not done well very often. One of the writers I really love that does it beautifully is Nicholson Baker, which is surprising, because as a straight, older, white dude, he doesn’t seem like he would be any kind of model for me. But his sex writing is very tender and funny and generous and playful, unlike certain male writers who I will not name. Writers who have contempt for women’s bodies, and women—that you can feel coming from every page. Nicholson Baker doesn’t feel that way. I had been reading a lot of novels where male writers got to write these really explicit sex scenes, and I want to see that more for everyone. It’s selective, it’s hard to find it. I always tell my students, “You want to write the story that you want to see and you don’t see.” So I wanted to create that, and I thought, “I’ll just see if no one stops me.” So at some point, that became part of the project, and every story except for one has a sex scene. So that was really important to me, and I was lucky that my publisher was all for it.

KW: I also wanted to talk some about dystopia, since some of your stories have these dystopian details that are part of the fabric of the story but not front and center. For example, in “Real Women Have Bodies,” there’s a brief mention of the universities shutting down. Do you think about dystopia as being part of the worlds that you build?

CMM: I am ultimately a very lazy writer, and I don’t like doing a lot of world building, and I don’t like doing research. So, I’m the least suited to write science fiction or dystopia, or historical fiction, which is what I’m working on now. I’m more interested in narrowing my focus and following a person, or two people, in a shifting landscape, so I don’t need to imagine how society would reconstruct itself in a literal way. And they’re all short stories, which makes it easier to keep that narrow focus.

KW: Yeah, the effect on one person who is slipping into a new normal.

CMM: Exactly. It’s weird. For example, when I watch the movie Children of Men, which I’ve rewatched more than I’ve watched any film, I’m always seeing new background details. The way the world building is done is so sideways, and it really works. If you’re paying attention, you see new details in the background. Everything is so fully conceived, and there’s no info dumping. The details are just built into the fabric. In some ways, it’s a medium thing and different with film, but I still like to think about that film. When I wrote “Inventory,” that was on my mind as I was writing it, like, “how do I create this thing in the background while foregrounding this woman’s physicality and very intimate experiences?” So that was a challenge I had with that story, but that movie was very helpful in thinking about it.

KW: Yeah, that movie is endlessly relevant, too.

CMM: And that’s the point with dystopia, right? It only gets more relevant.

KW: Right. Before we go, how is the historical fiction writing going?

CMM: Well, it’s not all historical, but it’s sort of this progression. I’m having to do research, which I don’t like. It’s weird because my wife is also writing a historical fiction novel, but she loves research. So she spends eight hours in the historical society and is so excited, like, “Look what I learned!” Then I have to google one thing, and I’m like [groans]. It’s a totally different instinct. But I was doing some research for this project and finding out really cool details and getting excited about the rich history and how it could work. For me, it was scary at first, and I just had to jump in. I wasn’t sure how to tell this woman’s story from a hundred-and-some years ago, but I just had to start it and keep moving with the structure. Then I could fill in the pieces, and that’s been going okay. But it’s been slow going. “Inventory” I wrote in two hours, and the final version was very close to the version I initially wrote. It was just inside of me and came out, which happens sometimes, whereas “The Resident” took me three years to finish. I wasn’t quite sure what it was about. So, the new piece is taking me forever. I’ve been working on it for a year, and now that I’m touring, there’s less time.

KW: Yeah, you certainly have enough on your plate.

CMM: Yeah, I probably won’t finish it until next year. But next summer I’ll be finishing my memoir, which will be my second book with Graywolf Press. And then I’ll have the Bard residency in the fall, so I’m hoping that will be enough time to finish.