The boy begins by saying he has killed a spider, a Goliath among spiders, a monster dangling from the ceiling on a strand of gleaming silk, the grossest thing he has ever seen.

The father asks how he has killed this spider.

The boy flinches. His misgivings are plain.

The father asks him again how he has killed this spider.

A book.

A library book?

From your shelf.

Which shelf?

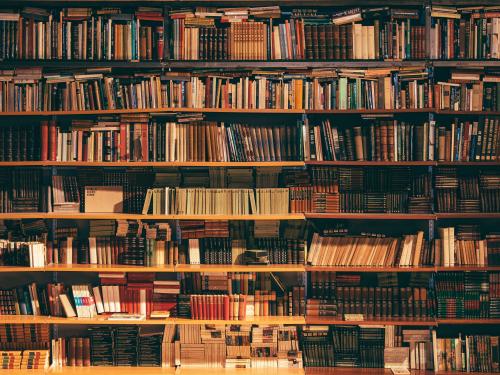

The boy leads him into the den and lowers his head. He points broadly at a bookcase, eight feet high.

The father asks, which book?

I don’t remember.

Which shelf?

I don’t remember. I put it back. I thought you’d be angry.

You used the cover?

No, I opened it up. I shut it inside.

The father imagines one of his first editions fouled by this unpleasantness. It is an abstract kind of panic.

He briskly flips through a few volumes of The Story of Civilization, reprioritizes, then inspects Ghost Stories of an Antiquary, Chronicles of Golden Friars, and Tanglewood Tales. He has decided that, with the way his shelves are arranged, the book in question must either be from “History” or “Horror.” The boy is only four feet tall, how high could he reach?

Are you mad, Daddy?

The boy has otherwise outgrown the use of “Daddy,” so the father recognizes it as a social calculation. No, of course not, he says.

After he puts his son to bed, he returns to leaf through further volumes. He feels as if he has inherited a minefield and must tiptoe accordingly. There is a sense of growing dread; each flip of the page could reveal the mangled spider, a stain with eight legs.

It does not turn up that night.

In the months that follow, the father tends to avoid the books from that case entirely. He’s read them already, at any rate, and if he never finds the dead spider, it will almost be as if it never existed. There are only so many years in a life, and although he bought each of these books with the intent of reading them more than once, he admits that there are many he will never have the chance to revisit, even in his forty or fifty remaining years. Still, there is the matter of this blackened page, locked in the bindings of an unknown tomb. Each time his son visits, he finds himself remembering and shivers as though someone has stepped on his grave.

Fourteen years later, in an empty nest, the father tugs the chain of his green banker’s lamp and is about to remove The World and the West from its slot on the shelf when, out of the blue, he remembers the missing spider. It’s been ages since he thought about it. He imagines it must have dried up by now, crumbled away into dust, leaving behind nothing but a slight bruise on the page. And yet he knows this is a false hope. He knows the dead creature remains, intact, plotting to catch him unawares.

He hesitates. It feels unlucky to tempt fate, and, in his loneliness, he has become quite superstitious. He is imagining the crumpled body suddenly behaving like the Black Spot from Treasure Island—a force of chaos, a death sentence, perhaps tied to some future misfortune of his son. For now, he lets the book be. If he really wants to read it, he can check out a copy from the library.

Now the father is eighty-one. Years ago, his son moved away to Alaska, heeding an opportunity at a leading fishery. At first, he dismissed his son’s choice but has come to acknowledge that the major markers of his own life were decided arbitrarily, at best. His son’s yearly visits are a source of great comfort, but the spaces in between are bleaker than the arctic winter.

In the mood for poetry, he eases Black Beetles in Amber from its notch on the shelf. He spreads back the calfskin cover, the marbled pages seem to ripple on their own, and in all of its awfulness, the flattened spider is revealed. The father’s heart skips a beat. Fingers of ice flutter across his shoulders. He swiftly shuts the book, but there is a rising wail beyond the limits of his hearing, the impression of invisible walls closing in around him. He is certain that at any moment the phone will ring, and it will be Alaska calling-—a disaster at the fishery, an avalanche, the storm of the century. Overwhelmed, he turns out the lamp and lies down on the parquet floor. He conjures doom and gloom, terror and horror, a darker and more personal nightmare than anything his shelves can offer.

Uncertain dreams give way to a wobbly awareness. The night, suddenly empty with silence. An old man, struggling to rise.