Whiteness is a dangerous concept. It is not about skin color. It is not even about race. It is about the willful blindness used to justify white supremacy. —Chris Hedges

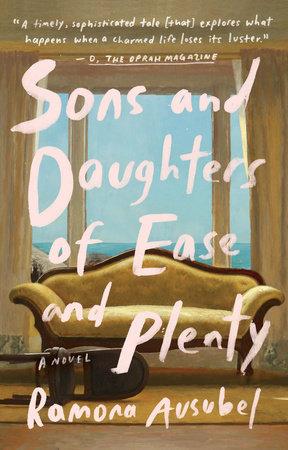

On the surface Ramona Ausubel’s second novel Sons and Daughters of Ease and Plenty is a summer romance about the affairs of wealthy people. However, beneath that surface runs a chilling commentary on the blindness at the core of whiteness.

The book opens with a sparkling scene in 1976 on Martha’s Vineyard. There, Fern, Edgar, and their three small children spend summers. Their idyll ends with a phone call informing them that their endless font of money has run dry. The book takes place over the seven days that follow, interspersed with chapters chronicling Edgar and Fern’s courtship. Along the way, Ausubel offers an anthropological look into white, upper-class America with dizzying descriptions of social mores, endless purchases, and dinner parties that realign the pecking order.

Ausubel embeds emotions in lushly appointed settings. The day after a funeral, Edgar’s mother “sat down beneath the hum of a violin concerto to scrub clean the silver that had touched the lips of the grieving.” In this society, men and women step into assigned roles, women locking their ambition away. When Fern is born, her mother looks down on “another perfectly wasted life. Maybe the girl would care about something along the way—art or history—but it would all be pressed out of her slowly until she was nothing but a woman, nothing but a mother.”

Fern and Edgar fall in love as the radical movements of the 1960s play in the background. A picture of white naiveté, “they celebrated with root beer floats when the Civil Rights Act was passed.” Edgar dabbles in Marxism and refuses to take part in his family’s business on moral grounds; however, he still lives off their money, which gifts him the time to peck away at a novel trying “to articulate his own wrongness.”

“Being rich had felt to Edgar like treading alone for all of time in a beautiful, bottomless pool,” Ausubel writes, yet when he loses that wealth, he is even more adrift. He starts an affair with a woman in an open marriage and tries to absolve himself by offering Fern to his paramour’s husband without asking for her permission first.

Fern retaliates by participating in a bizarre ritual: a fake wedding to cheer up Alzheimer’s patients at a local nursing home. The volunteer groom is a giant who convinces her to join him on a cross-country trip.

With Edgar and Fern on their respective journeys, their children are forced fend themselves, eating out of cans and living in the backyard. In one chilling scene, they discover a dead fawn and carry un-popped popcorn “outside with their cupped hands, slowly, slowly transporting a little bit of life out to the dead. They poured the seeds over the fawn and pressed them into her soil. ‘Grow,’ they said, ‘Grow, grow.’”

Nine-year-old Cricket insists that they still go to school, because she is under the thrall of a new teacher, Ms. Nolan. Nolan teaches Native American “history” by having the students act out imaginary romances between white settlers and Indian princesses in the West. Cricket never knows that “in another version of their house and yard before anything had been built there, before there was such a thing as the city, a non-imaginary Native family had lived in this same spot.”

The book revolves around this denial that privilege is a result of white violence. Fern’s family smugly claims abolitionists among their ancestors; however, “they did not speak of the fact that in order for a family to free their slaves they must first have owned them. They did not stop spending the money that had been earned with the help of bodies, bought and sold. It was that money that furnished every single thing in their good American lives.”

This privilege not only provides them with imported furniture, sailboats, and summers away, but also saves their lives as others perish. When Edgar is drafted, his father puts in a call, as the wealthy do, and Edgar ends up in Alaska, typing condolence letters to the families of the dead; while tens of thousands of Americans died in Vietnam, Edgar sulks in Alaska. He reports, “All there is, is nothing here. Whiteness,” never realizing that it is that very whiteness that saves him.

Sons and Daughters of Ease and Plenty

by Ramona Ausubel

Riverhead Books, 2016

$27 Hardcover; ISBN 9781594634888

320 pages