As an undergraduate at the University of California Berkeley, Myriam Gurba developed an eating and exercise disorder in the wake of a sexual assault. One day, she passes out in the school gym. As she comes to, an employee asks if she’s epileptic. She replies, “I’m Mexican.”

Gurba’s memoir Mean isn’t a coming-of-age story about discovering an authentic self. Rather, it’s a hybrid text that blends humor, true crime, poetry, and art criticism to enact how identity is apparitional. It is created and destroyed in thousands of violent and daily collisions between one’s own sense of self and the outside forces of educators, rapists, bullies, and racists. Identity is slippery and contingent, and its flickering nature allows for resistance and creativity. Gurba writes, “I didn’t know Mexicans were Mexicans, a category some mistake for subhuman . . . Today I understand that words are for everyjuan, but that not everyjuan is for every word.” In her humorous portmanteaus, Gurba claims and mobilizes language, making it playful and rebellious.

Throughout the book, Gurba claims the status of someone who is “mean,” even as her definition of the word shifts and changes. She writes, “Being mean isn’t for everybody. It’s best practiced by those who understand it as an art form. These virtuosos live closer to the divine. They’re queers.” The queer art of meanness is an artistic skill and a means for survival: “I know I can be mean, but I also want to be likable. I just don’t want to be so likable that anyone wants to rape me.” Being mean creates a protective screen—one that ultimately fails.

The summer after her freshman year of college, Gurba is attacked by a stranger. A few months later, the same man rapes and murders a migrant worker named Sophia. Gurba struggles with how to write about the violence they both experienced: “Wrecking her makes him feel like she belongs to him. We may feel that because we are privy to the wreckage she belongs to us too, but she does not.” How can writers contend with sexual violence without making rape into a spectacle and without reobjectifying the victim?

While the art of meanness didn’t protect her from being raped, Gurba leverages meanness in the aftermath to assert agency through textual and generic manipulations. She shifts from prose to poetry, makes a found poem out of Sophia’s autopsy report after declaring “I hate found poems. Found poems are so tacky,” collages narrative time, and, perhaps in the ultimate declaration of sovereignty via meanness, makes a joke out of her rape: “A stranger chose me to rape. / There was no nepotism involved. / Basically, I got raped for real. (I’m being cheeky here.) / Stranger rape is like the Mona Lisa. / It’s exquisite, timeless, and archetypal. / It’s classic. I can’t help but think of it as the Coca-Cola of sex crimes.” The butt of the joke is that Western culture is a culture born of violence in which “high art” is the same as a bottle of Coke.

An accomplished spoken word artist, Gurba shifts from prose to poetry, opening up lyric spaces where narrative time is held at bay. In these spaces, the logic of the narrative gives way to association and images. She writes, “Some of us use metronomes to tell time. / Some of us use baseball bats as metronomes. / Some of us use rape to tell time.”

Not only does Gurba queer genre, she also plays with memoir tropes such as the conceit of coming-of-age via education. Instead of progressing linearly through her education, she seizes on scraps of scholarship and canonical works of art and transforms them into tools in her survival kit and fodder for her own feminist art. For example, she takes a phrase from Walter Benjamin—“the chaos of memories”—and maps her own experience of trauma onto it. She writes, “My spirit latches onto it and wraps its arms around its queer, hairy legs.” She also transforms Duchamp’s urinal into a vaginal vessel that offers her access to redemption by turning trauma into art: “If Duchamp could place a urinal in an art gallery and thus elevate it, I can do the same thing with myself. By redefining my little molester as a sculptor, I redeem my molestation. I secrete English, Spanish, and tears, but, like a urinal, I also function as a vessel. I hold sadness, language, memories, and glee.” In this passage, Gurba takes on the position of an art object, one made by her molester, but unlike an art object, she is not fixed and static. Instead, she holds—and disperses—language, meaning, and story. Gurba describes coming into her own as an artist as using art “to work out touch gone wrong.” Art becomes a way of thinking through her experience with violence and asserting agency over it, albeit a highly idiosyncratic form of agency.

With no access to agency, Sophia haunts the narrator. Gurba feels a strong connection to the murdered woman but struggles to comprehend the exact nature of their connection. One way she understands it is through the horror movie trope of the “final girl”: “This girl gets to live, but she understands that her job is to tell the story.” Mean is the story that gets told when the final girl is Mexican, queer, and mean. It’s not a triumphant story of survival, rather it’s a defiant, hybrid text that refuses to let anyone off the hook and resists the falsity of closure.

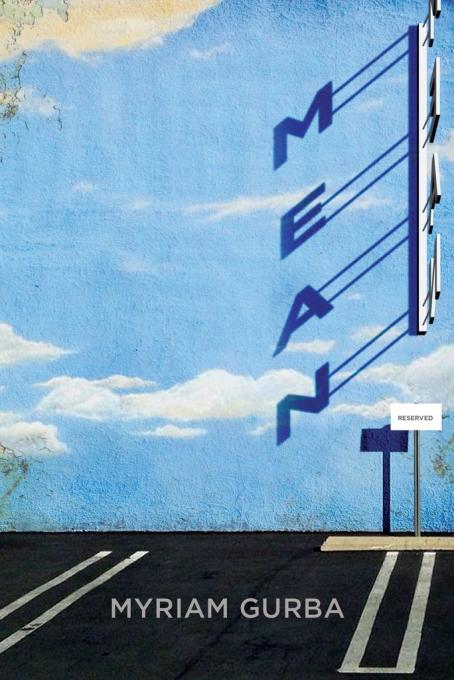

Mean

by Myriam Gurba

Coffee House Press, 2017

$16.95 Softcover; IBSN: 9781566894913

192 pages